How UKIP’s election strategy is boosting Theresa May’s chances of a big majority

In the aftermath of the 2016 Brexit vote, UKIP seems to have lost much of its original purpose and is unlikely to repeat its 2015 vote share at the 2017 General Election. But, Ron Johnston, Charles Pattie and David Rossiter argue, it may yet have an important – if indirect – impact on the election result. UKIP is trying to demonstrate the strength of support for Brexit by standing candidates in Labour-held but UKIP-leaning seats, and constituencies where the Conservative incumbent opposed Brexit. In some Labour-Conservative marginals, meanwhile, it has not fielded a candidate at all. In this way, the party is boosting Theresa May’s chances of a big majority.

Pounding the streets: a Ukip campaign car in Hampshire, 2013. Photo: Stephen West via a CC BY 2.0 licence

After its striking result at the 2015 UK General Election (with 12.9 per cent of the votes cast in Great Britain, the party was the third most popular in the country) and having achieved its goal of forcing the government to hold a referendum on the UK’s membership of the European Union, UKIP seemed to be on a roll. But the vote for Brexit deprived it of much of its original purpose. To remain relevant, it needed to identify new roles on the British electoral scene ready for the next scheduled general election in 2020. One of those it promoted was to hold the government to account, to ensure that the Brexit negotiations resulted in an outcome consistent with the party’s goals (on reducing net immigration, for example); another was to continue to seek support among working-class voters who felt increasingly alienated from and ignored by the major political parties – notably Labour – many of whom voted for Leave in the 2016 referendum.

And then Theresa May called an unexpected snap general election for 8 June 2017. Her Conservative government had only a small overall majority in the House of Commons and she was seeking a larger mandate not only for the negotiations with the European Union but also to ensure that the deal she returned with would win Parliamentary approval. On the latter, it was clear that the Liberal Democrats and the Scottish National Party would oppose any deal, and although the Labour party had indicated its acceptance of the referendum outcome there were fears that many of its MPs, especially those who had supported the Remain campaign, would challenge aspects of the negotiated deal.

So what role could UKIP play in the 2017 election?

After the 2015 general election there was a smaller number of marginal seats than at previous post-1945 contests. There were, however, 42 seats where Labour’s candidate defeated a Conservative opponent by less than ten percentage points, and the Conservative campaign is focused on winning most of those as the main route to the desired larger Commons majority.

One feature of many of those marginal seats is that UKIP’s 2015 vote share was larger than Labour’s majority. Opinion polls since the Brexit vote suggest UKIP has lost substantial support having achieved its major goal, so if many of those who voted UKIP in 2015 switched to the Conservatives, as the party implementing a ‘hard’ Brexit along UKIP’s preferred lines, this could markedly assist the Tories to defeat Labour’s candidates. But some voters might remain loyal to UKIP, or abstain, or vote for another party, and thereby make that task harder.

In part to avoid that situation, UKIP has decided not to field candidates in a substantial number of seats in 2017. Of the 632 constituencies in Great Britain it has nominated candidates in only 377 and in the 232 won by Labour in 2015 it is fielding only 157, so that the Conservatives face a straight fight with Labour in 75. How influential might that decision be on the outcome in the contested marginal seats?

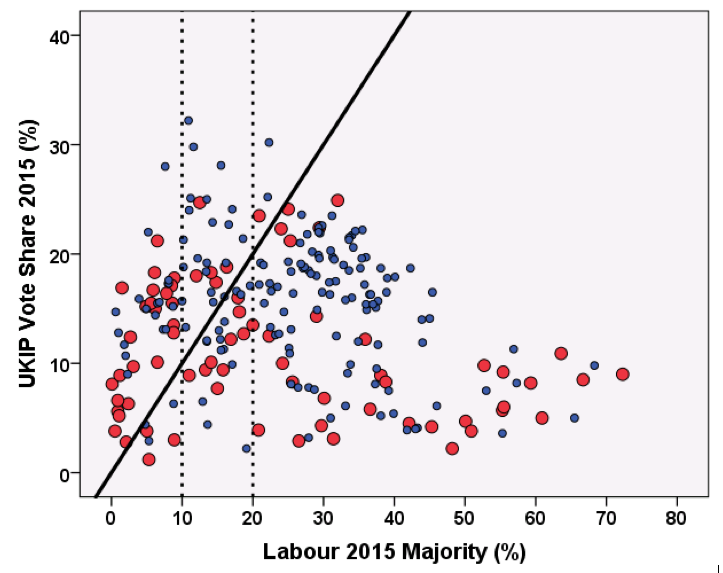

The first graph shows all 232 Labour-won seats in 2015, arranged along the horizontal axis according to the majority then – the further the seat is to the right, the larger the majority. The vertical lines separately identify the marginal seats (the left-hand column; majorities of less than 10 points), the fairly safe seats (the central column, margins of 10-20 points); and the very safe (margins of 20 points or more). On the vertical axis seats are arranged according to UKIP’s 2015 share of the votes. Constituencies with a UKIP candidate in 2017 are shown in blue: those with no UKIP candidate are in red. The diagonal line indicates where UKIP’s 2015 vote share exactly matches Labour’s 2015 majority.

In all constituencies above the diagonal line UKIP’s 2015 vote share was greater than the Labour majority, so the greater the proportion of those former UKIP supporters who switch to the Conservatives in 2017 the greater the chances of a Conservative victory there. UKIP has contributed substantially to those chances by deciding not to field a candidate in many of them, especially the marginal seats. It is contesting many of the seats where it did well in 2015 – including most of those where its vote share exceeded 20 per cent (including Hartlepool and Walsall North, which are Labour-held marginals). But in many of the tight Labour-Conservative contests it has enhanced the Conservatives’ chances of victory by its decision not to fight the seat this time – it is not contesting the City of Chester and Wirral West seats, for example, or Brentford & Isleworth and Ealing Central & Acton, all of them won by Labour from Conservative opponents in 2015 by a majority of less than one percentage point. The main option for UKIP’s 2015 supporters in those constituencies is either to vote Conservative or abstain; if a large proportion vote Conservative this time, Labour could lose many of those seats even if its own vote share holds up.

Elsewhere, in the seats to the right of the diagonal line, especially the fairly safe and safe constituencies where the Conservatives have less chance of unseating Labour, UKIP has followed its general aim of seeking to replace Labour in many of its heartland seats. It is not fielding a candidate in many of the seats where it won less than 10 per cent of the votes in 2015 – the red dots. But in those where it performed relatively well – a large cluster of blue points where it gained about 20 per cent support in 2015 – it is contesting the seat again. Most are safe Labour seats – many of them northern working-class town (constituencies such as Blaydon and Gateshead in the Northeast, for example, Blaenau Gwent and Swansea East in Wales, Sheffield Heeley, and Wigan) – where UKIP is clearly seeking to extend its electoral base.

What about UKIP’s policy for Conservative-held seats? Here, its concern is that over half of Conservative MPs voted for Remain in the referendum, and while most have reconciled themselves to Brexit a number could create difficulties for the government as the negotiations proceed. If UKIP could replace them that might remove such potential problems – and if it couldn’t, which is very likely, a strong performance locally could convince the new Conservative MPs that their voters supported Brexit and they should act accordingly. (Conservative Home has a list of how Conservative MPs voted at the referendum.)

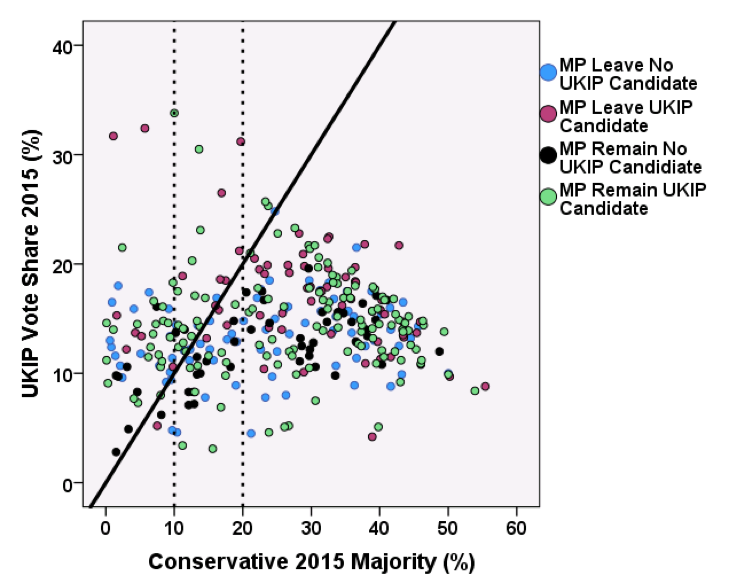

The pattern of UKIP 2017 candidacies in Conservative-held seats clearly illustrates that policy. UKIP is contesting 68 of the 147 seats where the Conservative MP voted for Leave, leaving 79 pro-Brexit Conservatives with no UKIP challenger for the pro-Brexit votes. Of the 184 seats where the Conservative MP voted for Remain, on the other hand, UKIP is fielding a candidate in 135.

The comparable graph to that for Labour shows that seat marginality also came into the calculations when UKIP was determining whether to field a candidate against the incumbent Conservatives. In the marginal seats, won by a Conservative candidate with less than a 10-point majority in 2015, UKIP is fielding candidates again where it performed well then (the purple and green points), irrespective of whether the local MP voted Remain or Leave; there is a UKIP candidate in South Thanet again, and also in Thurrock, Plymouth Moor View, and Telford, for example. But across most other constituencies there is no link to the margin of a Conservative MP’s victory in 2015: some where it was small have no UKIP candidate facing them in 2017, even though they voted for Remain; others with a similar majority face a UKIP contest. (Tania Mathias in Twickenham, defending a majority of 3.3 per cent, is not facing a UKIP challenger, for example, but Gavin Barwell, who won Croydon Central by only 0.3 per cent in 2015, is.)

How those who supported UKIP in 2015 decide to vote in 2017 is crucial to the outcome of Theresa May’s gamble that a general election now will deliver a substantial majority for a Conservative government. In many of the marginal seats that she hopes to win from Labour UKIP is assisting in that drive by deciding not to field a candidate – a policy that could well ensure that many of those seats are won by the Conservatives. Where the Conservatives are defending seats, UKIP’s main policy has been to contest those where the local MP voted for Remain; this is very unlikely to affect the outcome there – the Conservatives will win again – but the victors will be made aware of the strength of local pro-Brexit opinion.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit.

Ron Johnston (left) is a Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Ron Johnston (left) is a Professor in the School of Geographical Sciences at the University of Bristol.

Charles Pattie is a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Sheffield.

Dr David Rossiter has worked in a research capacity at the Universities of Sheffield, Oxford, Bristol, Leeds and Essex. He has been involved in the redistricting process both as academic observer (for example The Boundary Commissions, MUP, 1999) and as advisor to the Liberal Democrats.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The authors refer to opinion polling and the decline in UKIP’s share, but there is a very important additional consideration to this and it makes it difficult to argue the cliche that it is all to do ith UKIP no longer having a role (or at least one perceived by many of its voters) – the decline does not appear to be specifically linked to the referendum ‘Job Done’ theory.

If you look at polling since the referendum it divides very neatly into two parts. The biggest part (from a month after the referendum to the calling of the General Election) shows that on average UKIP did NOT decline from its just-under-13% score at the 2015 General Election. In fact the most usual figure for UKIP in that period was…13%. Then with the calling of the election, the figure has indeed fallen dramatically in just a few weeks. If you check the ukpollingreport.co.uk site you will see all the polls conducted in that period and a very convenient listing of all to the right of the opening page. If you look carefully, you will see that UKIP ROSE after the 2015 election with the Tory antics surrounding the referendum, and then fell a few points after the vote – back indeed to that 13% where it stayed pretty solidly.

This is important because it tends to point to a very simple success for the Tory position (which is popular even with a large % of Remain voters) – ‘we need to get on with it, and just get out’. As a former Vice Chair of UKIP and its leader on the London Assembly a decade ago, I have had many contacts this time round who say to me: “May is promising to get us out, voting UKIP might let Labour in in my seat, so I am lending the Tories my vote”.

The authors suggest that the ‘vote for Brexit deprived it [UKIP] of much of its original purpose’. The purpose is to get the UK out of the EU and it surely will come as no surprise to learn that we are still in the EU. The vote was the first stage, and cynics (and all sensible UKIP voters) have a wary eye on a Remainer like May, leading a party composed mostly of Remainers which has spent a generation or more attacking and vilifying its own Leavers (or even just those non-Leavers who had eurosceptic views), driving them out and marginalising them. The story for this General Election relates simply to giving someone a majority to do a job against another party which appears likely to try and scupper it. It remains to be seen whether the Tories will indeed do the job, which is why UKIP has never been more needed and why its job is not done.

The Tory cry in 2018 or 2019 of: “Our hands are tied, we can’t leave the EU after all,” cleverly dressed up via the classic Beneficial Crisis, neatly fabricated by all stakeholders, is awaited with interest…

In a French car?