Audit 2017: How democratic are the central institutions of devolved government in Scotland?

Devolved government in Scotland started as a radical innovation in bringing government closer to citizens, and its development has generated great expectations including strong pressures for and against the Scottish Parliament and government becoming the core of a newly independent state. As part of the 2017 Audit of UK Democracy, Malcolm Harvey and the Democratic Audit team explore how democratically and effectively these central institutions have performed.

MSPs’ offices at the Scottish Parliament. Photo: Cowrin via a CC-BY-NC 2.0 licence

This article was published as part of our 2017 Audit of UK democracy. We have now published: The UK’s Changing Democracy: The 2018 Democratic Audit with LSE Press, available in all ebook formats. You can download the whole book for free, and individual chapters, including a fully revised version of this article.

What does democracy require of Scotland’s devolved Parliament and government?

• The legislature should normally maintain full public control of government services and state operations, ensuring public and Parliamentary accountability through conditionally supporting the government, and articulating reasoned opposition, via its proceedings.

• The Scottish Parliament should be a critically important focus of Scottish political debate, particularly (but not limited to) issues of devolved competence, articulating ‘public opinion’ in ways that provide useful guidance to the government in making complex policy choices.

• Individually and collectively legislators should seek to uncover and publicise issues of public concern and citizens’ grievances, giving effective representation both to majority and minority views, and showing a consensus regard for the public interest.

• The Scottish government should govern responsively, prioritising the public interest and reflecting Scotland’s public opinion.

Scotland’s law courts and legal system have always been separate from those in England and Wales, and culminate in the High Court in Edinburgh. However, the UK Supreme Court remains the key legal arbiter of relations between the UK and Scottish governments.Many of the founding ideas for Scotland’s parliament and government were defined by the Scottish Constitutional Convention (1989-95), and implemented in the Blair government’s devolution settlement overwhelmingly endorsed by Scottish voters in 1997. The core institutions are a Scottish parliament of 129 MSPs, elected by a broadly proportional representation system (the additional member system). A Scottish Executive was set up to run all the devolved policy areas, using a directorate structure (instead of the separate departments found in Whitehall). Its policy responsibilities have steadily expanded and the now Scottish Government supervises the 60 per cent of spending in Scotland (£41 billion) that are devolved functions. The key areas excluded from their control – and which would accrue only to an independent Scotland – remain social security (£18 billion), most major taxation, defence and foreign affairs. Most domestic spending (on education, health, transport, housing, local government, the economy etc) is devolved. The government is currently headed by the Scottish National Party (SNP) leader, First Minister Nicola Sturgeon. She has a small cabinet (12 members), plus another 13 ministers, all drawn from the Parliament.

Recent developments

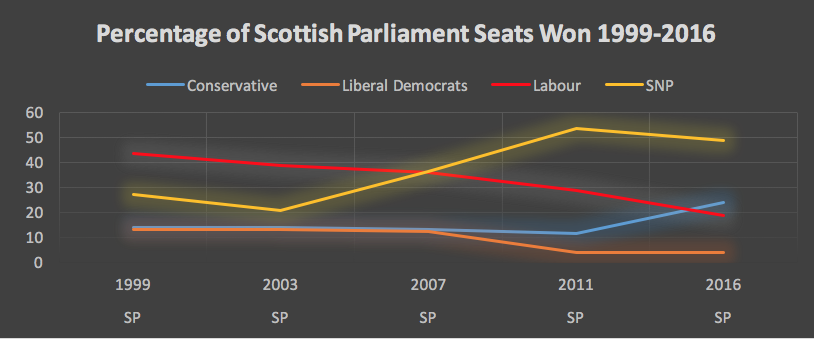

Despite electing MSPs via proportional representation, which tends to stabilise political alignments, Scottish politics has undergone a period of significant political and constitutional upheaval over the past half-decade. In 2011 the SNP returned 69 of the 129 MSPs – a majority government, for the first time – providing the crucial catalyst for Scotland’s independence referendum in 2014. The SNP proposition that Scotland should secede from the UK (also supported by the Greens) was opposed by all the main UK parties in Scotland and was defeated by 55 to 45 per cent.

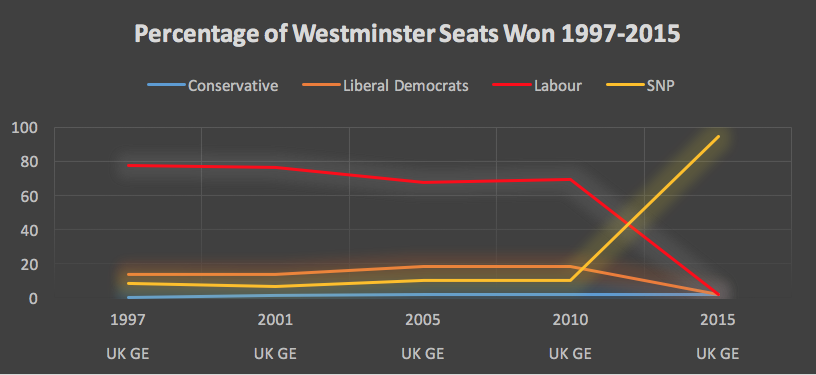

Nevertheless, far from killing off the SNP and their raison d’être, the strong campaigning momentum of the referendum period and its aftermath saw SNP membership increase fivefold, from 25,000 before the referendum to around 125,000 in the six months after it. At the UK general election in 2015, the SNP went on to increase their seats from six in 2010 to 56 of Scotland’s 59 seats, taking 49.97% of the vote in the process. This was a high water mark and in the May 2016 Scottish Parliament election the SNP won 63 seats, falling two shy of the 65 required for a majority, but retaining government office.

The Scottish independence referendum also began critical changes in the fortunes of Scottish Labour and the Scottish Conservatives. Labour was first ousted from control of the Scottish executive in 2007, and its subsequent history has been nothing short of catastrophic. Since then the party has had nine different leaders (three of those in a caretaker role) and its previous dominance of Scottish politics has rapidly leached away. A key stage was reform of the electoral system for Scottish local government, often Labour-dominated, with the single transferable vote introduced by the SNP with Liberal Democrat and Green support in 2004. At three elections (2007, 2012 and 2017) Labour’s previously dominant control of councils and councillors has been drastically eroded by the SNP. Increasingly without its traditional hegemony in central Scotland’s local authorities, Labour’s decline accelerated under PR elections for the Scottish Parliament. And Figure 1 shows how suddenly and completely their Westminster predominance was completely terminated in 2015, with the party losing all but one of the 41 seats it held in 2010. For a party that had dominated Scottish politics for nearly half a century, this has been a stunning reversal of fortune, accentuated by weak UK Labour leaders (Miliband and Corbyn) who had little electoral appeal in Scotland – though signs of this decline were already apparent under Gordon Brown’s premiership.

Meanwhile since the 2014 referendum the Scottish Conservatives have staged a significant revival, becoming the main opposition party to the broadly social democratic SNP. As a result of the proportional electoral system that they had continually opposed, the Conservatives have moved sharply back from the electoral decline of the 1990s, largely because their clearer and complete opposition to independence suddenly projected them as the safer option in defending the UK union. Labour’s once equally strong unionism was squeezed in the referendum campaigns by the SNP’s embrace of social democratic approaches, and divisions amongst Labour and left/green voters, members and trade unionists on how to vote. The party leadership found themselves in a constitutional lose-lose situation between the SNP’s clear nationalist option and the Conservatives’ unabashed Unionism. Labour has tried to float a position somewhere between the two, discussing increased autonomy, ‘devo-more’, and, most recently, even federalism. But the issue has become so polarised that there are now few voters in the middle ground. Labour’s prospects for future recovery appear slim.

Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats (SWOT) analysis

| Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|

| The Scottish Parliament has long held itself to be a parliament that is transparent in its operation, and the stringent measures it took to provide for registering interests of its members meant that it has largely avoided the negativity that befell Westminster in the wake of the MPs’ expense scandal. | Parties in the Scottish Parliament operate strict party discipline, like the House of Commons. MSPs rarely rebel on whipped votes. During the 2011-16 majority SNP government, many critics complained that rigorous SNP discipline reduced the Parliament to a residual role akin to the stunted functions of the Westminster Parliament –subject to the dominance of the executive. |

| As a key aspect of set-piece politics, the weekly jousting session that is First Minister’s Questions provides opposition parties with the opportunity to hold the government to account. | The committee system of the Scottish Parliament, established to fulfil the function of both Westminster subject and select committees, has proved ineffectual in scrutinising legislation and holding government ministers to account. Members are assigned to committees based just on party strength in the wider parliament. |

| The establishment of family friendly hours – parliamentary business takes place from Tuesday to Thursday, 9am-6pm, with infrequent exceptions – means that members have a clearly established working pattern, allowing for better work-life balance, the ability to spend more time with family or other outside interests (one MSP is a qualified referee and regularly features at Scottish and European games). | First Minister’s Questions provides a set-piece session, albeit in a tired format. But it does not clearly fulfil objectives of enhancing scrutiny or accountability. Questions and answers frequently revert to partisan bickering, especially on the unresolved constitutional questions around independence. |

| Electronic voting allows for decisions to be made quickly and records to be announced without the need for physical divisions that operate in the House of Commons. The Parliament also has modern IT built into all its operations. | The Additional Member System for electing MSPs creates a distinction between constituency and regional list MSPs, although issues around ‘two classes’ of members are less evident than in Wales. Some list MSPs have been accused of ‘targeting’ citizens cases in a single local constituency of their region, with the next parliamentary election in mind. Potentially then, their regional constituents elsewhere might not be as well represented as those in the target constituency. |

| The operation of the Additional Member System has created a closed party system in Scotland. No new parties entering the legislature since 2003. There is no official ‘threshold’ to gain list MSPs (as there is in the operation of the German AMS electoral system). But because top-up regions are quite small, parties normally need to secure between 5 and 9 per cent of the list vote, in order to secure MSPs at this stage. | |

| The Parliament has few ethnic minority MSPs. The first was elected in 2007, and only four have succeeded ever, each initially elected as regional members for Glasgow. |

| Opportunities | Threats |

|---|---|

| The vote to leave the European Union has altered the dynamics of the Scottish constitutional debate. Given the nature of the ‘reserved powers model’ of devolution which established the Scottish Parliament, the ‘repatriation’ of powers from Brussels may provide the Scottish Parliament (and government) with the opportunity to accrue most of these powers, providing it with extensive competences. | Scotland has only a small, uni-cameral legislature. There is no upper chamber to act as a check or balance on the Parliament mis-operating or over-reaching its powers. |

| The return to a new SNP minority government from 2016 may mean that parliament can reassert itself, regaining a clearer role in scrutinising government legislation and holding the government to account. | With or without independence, the Scottish Parliament faces major issues about its capacity to deal with the significant increases in powers that have been delivered or are promised. When 25 government ministers and three different main opposition party front benches are removed (at least another 35 MSPs here), only a limited number of members remain to fill existing committee seats. (The problem would worsen post-independence, with more ministers and committees needed for five main additional functions). |

| The Presiding Officer’s ‘MOT’ review of the Scottish Parliament and willingness to actively examine the operating procedures is both timely and a recognition that there are ways in which the parliament can improve. |

Has the Scottish Parliament matched its own democratic ideals?

Following the success of the devolution referendum in 1997, a Consultative Steering Group on the Scottish Parliament was established to provide recommendations on how the parliament should operate: how it would be elected, the Standing Orders that would operate, and the key principles it would operate under. They provided an ambitious agenda for an apparently more consensual democratic approach. A first ‘key principle’ was (unexceptionally) that the Scottish Executive (now Scottish Government):Has the Scottish Parliament matched its own democratic ideals?

• ‘should be accountable to the Scottish Parliament, and the Parliament and Executive should be accountable to the people of Scotland’.

Three more far-reaching ‘key principles’ required that the Scottish Parliament:

• ‘should embody and reflect the sharing of power between the people of Scotland, the legislators and the Scottish Executive;

• should be accessible, open, responsive, and develop procedures which make possible a participative approach to the development, consideration and scrutiny of policy and legislation;

• [and] in its operation and its appointments should recognise the need to promote equal opportunities for all’.

On each of these three measures, the picture is rather mixed. Power-sharing between the executive and the legislature was most obvious during the SNP’s period of minority government between 2007 and 2011; and, again, since the 2016 election. These periods gave the Scottish Parliament a clear role in adapting, challenging and scrutinising government proposals. During the first two sessions – under the Labour-Liberal Democrat coalitions – parliament’s role was more limited, though private members’ legislation piloted by Tavish Scott and Tommy Sheridan were passed into law.

However, from 2011 to 2016 there was an overall Scottish National Party majority in the legislature. This was a period characterised by much more in the way of executive dominance (more in line with the ‘Westminster system’ model). The Scottish Parliament was reduced to a rubber-stamping role as the (incredibly disciplined) SNP government utilised its majority of MSPs to full effect.

On accessibility, the Scottish parliament appears to score more highly. It has a well-utilised public petitions committee and a clear and transparent process of legislating, and it symbolically meets inside a building in which most rooms are glass-fronted. However, public engagement in its elections continues to hover around the 50 per cent mark – significantly lower than the level of UK elections (though the independence referendum did see a record 84% turnout).

When it was established in 1999, the Scottish Parliament was one of the most gender-balanced parliaments in Europe, with only the Scandinavian states returning more female representatives. However, since then, and despite significant (but voluntary) mechanisms being adopted by several political parties, female representation has fallen. Ethnic minority representatives, and those who identify as having a disability, have also failed to become MSPs in any significant numbers, so the parliament’s success on promoting equality has been limited here. But it does maintain ‘family friendly’ working hours, with almost all parliamentary business taking place from Tuesday to Thursday in office hours. This allows MSPs to spend more time with family, their constituencies or outside interests – one MSP is a qualified referee and regularly features at Scottish and European games. Chamber business very rarely extends beyond 6pm – in sharp contrast with the late-night sessions that are frequently a part of the House of Commons business.

In terms of accountability, MSPs themselves have to adhere to a strict Code of Conduct, and the Standards Committee can investigate any breaches of this. Scottish Government ministers are required to respond to questions and appear in front of parliamentary committees regularly in order to provide information on their brief. However, ministers can be more or less accommodating – and the questions can be more or less pointed – depending on the nature of the query and the party which is asking it. There is a vigorous First Minister’s question time.

On becoming Presiding Officer after the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, Ken Macintosh announced that the parliament should undergo a ‘MOT’ to determine how well it operated and what could be improved. A Commission due to report in June 2017 will examine the ways in which the parliament can:

• be assured it has the right checks and balances in place for the effective conduct of parliamentary business;

• increase its engagement with wider society and the public; and

• clarify its identity as distinct from the Scottish Government.

Is Scotland a ‘dominant party system’?

The recent electoral dominance of the SNP led several political commentators and politicians – most notably Adam Tomkins, the newly-elected Conservative MSP – to complain that Scotland has become a ‘one-party state’. This characterisation is clearly flawed. A one-party state is a very different thing from ‘a dominant party system’, where regular competitive elections are held, but the same party always wins – as happened in Scotland in the period of Labour hegemony. But what this exaggeration does point to is that the relatively small Parliament is easily dominated by the executive if one party has an overall majority. For instance, in the period 2011-2016, when the SNP formed a majority government, this status guaranteed the party a majority of the institution’s committee convenorships (important for determining the business and agendas of committees) and, crucially, a majority of members on each committee. So the government not only had a majority in the chamber – where votes on stages one and three of legislation take place – they also had majorities in committees, where stage two is debated and amendments raised. This repetition of the Westminster model (despite PR elections) was accentuated by loyal SNP backbenchers keen to assist the government’s agenda.

Scotland, Brexit and a second referendum

The UK-wide vote to leave the European Union in June 2016 contrasted strongly with Scotland’s electorate voting 62% to 38% to remain in the EU, highlighting a clear divergence in public attitudes in Scotland from those in England and Wales. The SNP argues that the fact Scotland will be forced to leave the EU with the rest of the UK, despite voting differently, shows that Scotland is not an ‘equal partner’ in the UK, and that its ‘voice is not being heard’. The referendum outcome also puts the issue of a second constitutional referendum ‘back on the table’, with the SNP arguing that ‘only independence’ can ensure that the Scottish electorate are not overruled by the wider UK electorate.

The SNP government produced a document which outlined options for Scotland to retain some form of access to the EU and attempted to get the UK government to examine them. However, the May government’s increasing momentum towards a ‘hard Brexit’ up to the 2017 general election produced only bruising rebuffs for Sturgeon’s suggestions. These led in turn to the First Minister announcing that a second independence referendum should be held before the UK leaves the EU in April 2019 – a timetable that has been flatly rejected by the Conservatives, who put the earliest feasible date as 2020 – by which time Brexit would be a fait accompli. In the short term, opinion polls show that Scotland’s voters are opposed to a second referendum, and would split quite evenly but so far not convincingly for independence. The polls also suggest that there is a limited link between support for membership of the EU and support for independence – meaning that the issue of Brexit may not be the tipping point that the SNP hope for. However, it is also true that the starting point for an extended debate is much more favourable now for the independence cause than it was at the start of the 2012-14 campaign.

Dr Malcolm Harvey is a Teaching Fellow at the University of Aberdeen and an associate fellow of the Centre on Constitutional Change.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/11/audit-2017-how-democratic-are-the-central-institutions-of-devolved-government-in-scotland/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Informations here: democraticaudit.com/2017/05/11/audit-2017-how-democratic-are-the-central-institutions-of-devolved-government-in-scotland/ […]

Very nice article, but may I make one small criticism? You write under ‘Threats’ that

“Scotland has only a small, uni-cameral legislature. There is no upper chamber to act as a check or balance on the Parliament mis-operating or over-reaching its powers.”

May I point out that many of the most democratic countries in the world – Norway, Sweden, Iceland, etc – are unicameral. Bicameralism is not an indicator of how democratic a system of government is – in fact, it is more likely to be a counter-indicator.