The Kremlin doesn’t promote autocracy – it simply trolls whomever it dislikes

Russia is often accused of undermining democracy, particularly in former Soviet states. The recent reports of Russian-sponsored hacking in the US have led some to go further and claim it is actively promoting autocracy. But Nelli Babayan argues that Vladimir Putin’s chief aim is to demonstrate Russia’s strength – and probably to undermine US and EU democracies, rather than trying to transform them into authoritarian states.

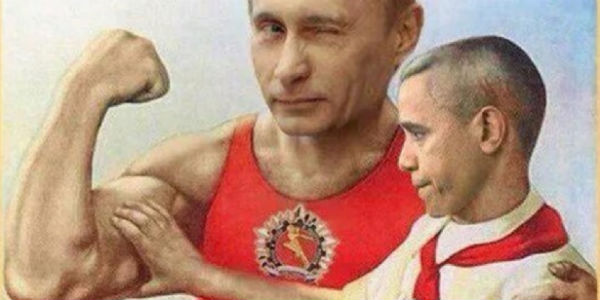

A Russian painting depicts Barack Obama admiring Vladimir Putin’s musculature. Photo: Mark Holloway via a CC-BY 2.0 licence

In recent years, many US and European officials and pundits have accused Russia of undermining democracy in its neighbourhood – and sometimes even of outright promoting autocracy. Often these claims are based on arguments that Russia wants to establish a new anti-democratic world order in the likeness of its own regime and its supposed support of “traditional values”.

From a scholarly point of view, these arguments may offer a neat way of categorising the complex and confusing troubles of the post-Soviet world and rising populism in Europe and the US. Yet detailed research into the domestic politics of post-Soviet countries shows that while Russia is not without blame, the stagnation of democracy is a by-product of the Kremlin’s attempts to ensure the survival of its own regime by counteracting factors it perceives as a threat.

Similarly, Russia does not create the domestic sentiments and troubles of the US or Europe – it merely attempts to capitalise on them. Despite vaunting Russia’s so-called traditional values as opposed to those of the zagnivayusii Zapad or “decaying” West, the Kremlin acts on an ad hoc basis in foreign countries, catering to groups which may feel disenchanted by their own domestic politics: France’s Front National, for example, or other far-right or far-left groups. While these actions may seem to undermine the liberal international order, the objective is rather to show that Russia can successfully disrupt that order – and for that order to function, Russia has to be integrated on its own terms.

But what difference does it make whether the Kremlin aims to promote autocracy, or merely to undermine whomever it deems unfriendly? The difference is the varying degree of vigilance of those on the receiving end of the potential meddling. Before Crimea’s annexation, the expectation was that Russia might slightly meddle in post-Soviet affairs, but that it would act according to the internationally-accepted playbook (or at least the West’s version). That is why its toolkit and attempts to shape the narrative beyond its immediate neighbourhood have perplexed some observers.

The extent of Russia’s meddling clearly transcended the borders of post-Soviet space when in 2016 a Russian state channel ran a false story that a Russian girl had been raped by Middle Eastern immigrants in Germany. The story became an international incident when Russia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs accused Germany of covering it up. This is unlikely to be the Kremlin’s last interference in Germany’s affairs, given the upcoming elections and Chancellor Angela Merkel’s unwavering criticism of Russia’s actions in Ukraine and Syria.

The revelation that Russia has been meddling in US elections through a hacking campaign has reinvigorated the argument that Russia is trying to undermine democracy. On 6 January, three US intelligence agencies published a long-awaited declassified report on Russia’s meddling in US elections. Based on this report, US media reported that Russia’s president Vladimir Putin “ordered an influence campaign in 2016 aimed at US presidential election” with the objective of helping Donald Trump to be elected as the President of the United States. Why? The report says that Putin wants to “undermine the US-led liberal democratic order” and that he dislikes Secretary Hillary Clinton “for inciting mass protests against his regime in late 2011 and early 2012”. According to the US intelligence agencies, there seems to be no doubt that Kremlin-sponsored hackers breached the Democratic National Committee’s computer security and dumped Clinton’s campaign emails to Wikileaks.

This conclusion is in line with Russia’s current modus operandi at home: enhancing and cultivating public sentiments currently useful to the Kremlin. Through the control and shaping of information on both traditional and online media, Russia has sought to legitimise its policies. The campaign is multidimensional since it attempts to legitimise its actions both domestically and internationally, and it is cyclical as domestically it heavily relies on already existing popular sentiments and perceptions.[1]

What seems rather hackneyed to a Russia-watcher is the evidence this declassified report brings. To substantiate its assessment, the report points to anti-Clinton coverage of the Kremlin-sponsored RT channel (for that matter not very different from the coverage by Fox News or Breitbart) and quotes Russian media and political personalities notorious for their eccentricity, expressing their delight over Trump’s elections. To be clear, in a recent survey Russian respondents called Trump’s election the most important event of 2016, second only to the increase of prices. For his part, president-elect Trump has downplayed these allegations attempting to focus on other issues, since “the age of computers has made it where nobody knows exactly what’s going on”.

While this story is still developing, it would stretch the evidence to describe Russia as an autocracy promoter acting against the US and the European Union – not least because the literature on the issue has yet to provide a clear understanding of what autocracy promotion is. Scholars have suggested it may include the deliberate diffusion of authoritarian values, helping other regimes to suppress democratisation, or condoning authoritarian tendencies. Yet some of these ideas may equally be ascribed to democracy promoters: for years both the EU and the US condoned the autocratic regimes of their allies in the Middle East and North Africa, based on their geo-strategic interests.

Research shows that even if Russia’s potentially confrontational policies may have contributed to the stagnation of democratisation among its neighbours, it does not seem interested in promoting a specific regime type in the way democracy promoters do. The stagnation of democracy in post-Soviet countries is the result of a set of factors, such as democracy’s lack of resonance there, high adaptation costs, protracted conflicts, weak institutions and illiberal elites. However, Russia still perceives the countries of the former Soviet Union as part of its inalienable sphere of influence – and Western policies, including democracy promotion, as a threat to that influence. Through economic sanctions, military threats and even through such formal institutions as the Eurasian Union, Russia has contributed to the stagnation of democratisation in its near abroad. It counteracted democracy promotion – or for that matter any other Western policy which it considered a threat to its geostrategic interests.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Dr Nelli Babayan is a Black Sea Fellow at FPRI, Non-resident Fellow at the Transatlantic Academy in Washington, DC and Associate Fellow at the Center for Transnational, Foreign and Security Policy at Freie Universität Berlin. She is based in Washington, DC. Her latest books include Democratic Transformation and Obstruction: EU, US, and Russia in the South Caucasus (Routledge, 2015) and Democracy Promotion and the Challenges of Illiberal Regional Powers (Routledge 2016, co-edited). She tweets at @nellibabayan

[1] Based on the author’s forthcoming article in the journal Europe-Asia Studies, Bearing Truthiness: Russia’s Cyclical Legitimation of its Actions.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] This article originally appeared at our partner site, Democratic Audit. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and […]

[…] States and Europe are set to undermine the survival of Putin’s regime. In return, the Kremlin has mobilized its own resources to undermine whomever it considers hostile in Europe and the United States. Second, there’s […]