Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes?

Mock elections help 16- and 17-year-olds understand how elections work. But do they make adults more likely to back lowering the voting age to 16? Erik Gahner Larsen, Klaus Levinsen and Ulrik Kjær looked at the 2009 local elections in Denmark, when a number of municipalities held mock elections alongside the real ones. They found that they did make over-18s more positive about votes at 16, though a stubborn core of older and more right-wing voters remained hostile to the idea.

Chante Joseph, 17, summarises the curriculum for life debate in the Youth Parliament sitting in the Commons Chamber, November 2013. Photo: UK Parliament/ Roger Harris via parliamentary copyright

Democracies put several constraints on who can participate in elections. The most salient constraint today is age – in other words, only adults should have the right to vote. Over time, most countries have settled on a voting age of 18, but in recent years there has been increasing debate in several Western countries about whether 16- and 17-year-olds should have the opportunity to take part in elections.

Those in favour of lowering the voting age usually argue that it is an opportunity to increase young people’s knowledge about elections and democracy. With that in mind, some countries have arranged mock elections for people who are not old enough to take part in the real one. Importantly, while the result of the mock election is irrelevant to the outcome of the real one, they attract attention from politicians and journalists.

In a new article published in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties we ask whether mock elections matter for democracy – beyond the impact on the adolescents themselves. More specifically, we examine whether people over 18 are more likely to allow young people to take part in real elections when they have seen them participate in the mock variety.

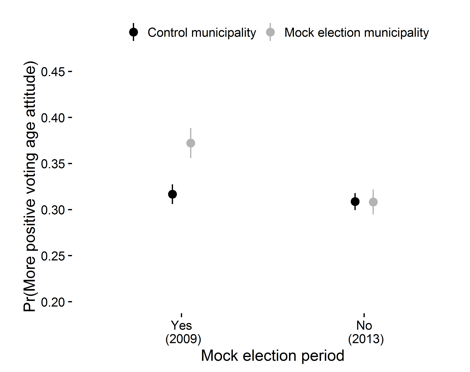

In order to test this, we used the context of the 2009 local elections in Denmark. Combining individual-level survey data and contextual data from 98 municipalities, we were able to study how support for lowering the voting age varies across different regions. Thirty-one of the municipalities arranged mock elections, and these municipalities were comparable to the areas that did not. To further ensure that any differences in the support for lowering the voting age depended on the mock elections, we used data from the 2013 local election, when no organised mock elections were held. It was therefore possible for us to test whether people were more positive toward lowering the voting age in those places that did organise them.

The figure shows, in line with our theoretical expectation, that people over 18 living in municipalities that organised mock elections in 2009 were more supportive of lowering the voting age. When adolescents are given the right to vote – even when the votes do not count in the real elections – people are more positive about the idea of letting young voters vote in the real election. The results from the 2013 campaign show equal levels of support among the municipalities, indicating that the effect of the 2009 mock elections did not persist and providing further evidence that they are unlikely to have happened because of more general regional differences.

Overall, we find empirical support for the expectation that an increased focus on reducing the voting age to 16 makes the public more supportive of the idea. However, while we do find evidence that letting adolescents take part in mock elections influences public attitudes towards the voting age, two further discoveries add nuance to the findings.

Figure 1

First, while we find that political events – in this case mock elections – shape peoples’ opinion about the voting age, they still have strong attitudes towards the issue and these are rooted in ideology and demographics. In particular, right-wing and elderly voters are more sceptical about lowering the voting age. This pattern is robust over time and across municipalities, showing that there are limits to how much differences in the political environment can potentially shape people’s attitudes.

Second, a majority of voters oppose lowering the voting age to 16. This finding is consistent with results from Norway, Australia and the UK. It seems that citizens’ perception of the ideal voting age is anchored toward the status quo, resulting in limited pressure from the public for lowering the voting age. In other words, the findings indicate that the public is, on average, against lowering the voting age, but that when people below the age of 18 are taking part in democracy – even when it does not count – the support for offering young citizens democratic rights is greater.

The focus on the ideal voting age will probably be debated in several countries in the coming years, especially given that 16-year-olds can now vote in some elections (for example, in Germany and Austria). Based on these findings, it is clear that attitudes towards the question are not set in stone and initiatives like mock elections can alter them.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit. It is based on ‘Democracy for the youth? The impact of mock elections on voting age attitudes’ in the Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties.

Erik Gahner Larsen (left) is research assistant at the Department of Political Science at University of Southern Denmark.

Erik Gahner Larsen (left) is research assistant at the Department of Political Science at University of Southern Denmark.

Klaus Levinsen (right) is Associate Professor at the Department of Sociology, Environmental and Business Economics at University of Southern Denmark.

Ulrik Kjær is Professor at the Department of Political Science at University of Southern Denmark.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

@democraticaudit with an interesting article, do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes? https://t.co/QReGYX7UQ1

Do 16-18 yo mock #Elections make adults more likely to back lowering the #VotingAge? : https://t.co/8ov9f2vZxv via @democraticaudit

Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes? https://t.co/utYlIKfNRe

Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes? @erikgahner writes https://t.co/X5Ku69v40Q

There are radical differences between one country and another on issues like this – the effectiveness of the test in Denmark would be nearly impossible to replicate in the UK, because there appears to be a greater commitment to public debate by the state in Denmark. When the Danes were debating the Treaty on European Union and holding a referendum 24/25 years ago (they had to vote twice as they gave “the wrong answer” the first time), the state distributed a huge number of copies of a rapidly translated Danish language version so that it could be available free to every voter. It was not even available in English when the major row about it occurred in the UK, well not until privately funded efforts were made by the new breed of EU opponents – but even then the state ordered libraries and schools to bar it, and it was refused all mention on state radio and tv (BBC). You could read it in German if you wanted, of course.

Any debates by 16 year olds in the UK would only get any form of media coverage out of a tired ‘state radio and tv’ style obligation – pushed out of the schedules as far as poss, with the researchers desperately trying to find some X-Factor style gimmick to make the programme sexy.

There is a further issue which is not thought through on this – in the UK, there has been much comment that 16 year olds may have swung the referendum for Remain. Unlikely given the stats but always possible. However this ignores the fact that until 2014 in the UK, the young were the second most eurosceptic group in Britain after the 65+ (just check out all the yougov polls for UKIP support and for pro/anti-EU stance. The view of young voters changed. You can see via yougov how and when this happened. Interesting stuff.

And a simple look at European countries shows that Golden Dawn (the Fascist Greek party) is strongest…among 16-25s. And the Front National in France is strongest among…the youngest voters.

So once it is established that the young are not simply cannon fodder for a ‘progressive’ world view, and CAN (just CAN) veer to extremes, the pleasure of this possibility will beat a hasty retreat among the Great and the Good in countries like the UK. Rest assured they are already aware…

“Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes?” | @erikgahner et al. (@democraticaudit) https://t.co/LRDPQXSyQZ

Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes? https://t.co/X5Ku69v40Q https://t.co/vsWqiSBUuh

Votes at 16: do mock elections make a difference to adults’ attitudes? https://t.co/vz9ig5m5P4