Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like?

Voters in the EU referendum could choose only between leaving and remaining – with no say on whether to stay in the single market, renegotiate a different deal or even integrate more fully with the EU. Lily Blake argues a multiple-choice referendum of the kind held occasionally abroad would have been less divisive, set a clear path for the government and better reflected the nuances of public opinion.

Image: Public domain

The EU referendum exposed several problems with the UK’s approach to direct democracy – from the manner of the campaigning to the handling of the aftermath. Some problems were caused by political agendas, some by a lack of constitutional guidelines for referendums. The experience has prompted many to consider whether referendums themselves are inherently flawed and problematic.

Yet the dichotomous nature of the EU referendum, whereby the voter could only choose between two options, is responsible for many of the problems that arose. Holding a multiple choice referendum instead of a binary one could have pre-empted them.

In the UK, the notion of a multiple choice referendum is unusual: we have never held one. But the idea is certainly not inconceivable. Between 1931 and 2000, 19 multiple choice referendums were held across the world. The issues ranged from deciding on a new national anthem (Australia, 1977) to prohibition (Finland 1931). A key challenge is the need to find a way of framing multiple choice questions in a way that avoids confusion and accusations of political bias. While introducing more answers adds a degree of complexity, Peter Emerson argues that multiple choice referendums lend themselves to more open questions than binary referendums. And open questions are easier to word in a neutral way.

Dichotomous referendums are divisive and extreme because binary choice discourages nuance. Most political beliefs rest somewhere on a spectrum. A binary choice, however, cannot account for this spectrum, resulting in an invariably stark result. When the options are ‘black’ or ‘white’, there is no choice to vote for ‘grey’. Emerson identifies binary decisions as being at the root of conflict, atrocity, and genocide throughout history. In ‘Defining Democracy’, he writes:

“Are you Catholic or Protestant? Serb or Croat? Hutu or Tutsi? These were all questions of war, as too was the choice during the Cold War: are you communist or capitalist?” (2012 [2002] p.17)

In other words, dichotomous referendums affect the public’s perception of societal cohesion, emphasising disagreement over consensus. The dichotomous nature of the EU referendum is a potential explanation for post-Brexit violence: those who thought themselves on the winning side still resorted to violence.

Any referendum question frames the remit of debate by outlining the acceptable options. The UK’s 2011 referendum on the Alternative Vote (AV) was treated as a referendum on proportional representation, but only gave voters the option to choose between AV or the current First Past the Post (FPTP) system. The referendum’s result ought to have demonstrated that voters did not want a system of proportional representation, but the result merely demonstrated that the electorate were opposed to AV. Had the question included more options, the result might have been different.

A binary choice referendum provides very little information on a voter’s stance. Many questions crucial to the UK and EU negotiations remained entirely unanswered by the EU referendum. Should the UK remain part of the single market or not? Should the UK leave by enacting Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty or repeal the 1972 European Communities Act? Should Brexit be ‘hard’ or ‘soft’? A vote to ‘leave’ the EU provided very little information concerning the sort of post-EU society the voter would prefer.

A government’s mandate to rule is derived from the electorate, making a direct referendum the most powerful mandate of all. Yet the lack of information gathered regarding the electorate’s attitude towards Brexit puts the government in a difficult position when it tries to enact voters’ wishes. Since referendums are an expression of public opinion, their success can be measured in terms of how much they enlighten politicians about the public’s preferences.

Multiple choice referendums have the potential to make sense of public opinion in a way that dichotomous referendums currently fail to. For example, the 1992 New Zealand referendum on electoral reform was able to discover not only if the electorate desired a new electoral system, but which one they would choose if the electoral system were to change – from a comprehensive list.

Another clear advantage (though it is often framed as a disadvantage) is that multiple choices make it harder to calculate a winning side.

The risk of voter fatigue and confusion

Some fear multiple choice referendums would be time consuming, lead to inconclusiveness and thereby cause referendums about referendums – leading to voter fatigue. These worries are reasonable, but misplaced. Several multiple choice referendum results have been decisive, including Finland’s 1931 decision to abolish prohibition, endorsed by 70.5% of voters. Because voters are offered more choice, a conclusive result has greater legitimacy attached to it.

Settling on a single question is also important: on a political conundrum such as EU membership, it would be possible to ask several questions on various areas of debate. A balance of public consultation on constitutional issues without resorting to excessive use of referendums is vital.

Arguably, New Zealand’s electoral reform referendums in the 1990s failed in this respect. They had another referendum on the same issue in 2011, barely 20 years after the first one. (Still, calls for a second EU referendum and the phenomenon of voter regret perhaps indicate that the dichotomous EU referendum of 2016 will be equally inconclusive.)

But Emerson argues that, in cases where multiple choice referendums would be inconclusive – such as constitutional questions in Ireland – binary referendums are even more problematic. For sensitive issues, the adversarial emphasis on ‘winning’ a binary referendum is dangerous, and resolving the issue without a referendum is vital in fostering social harmony.

A better EU referendum question

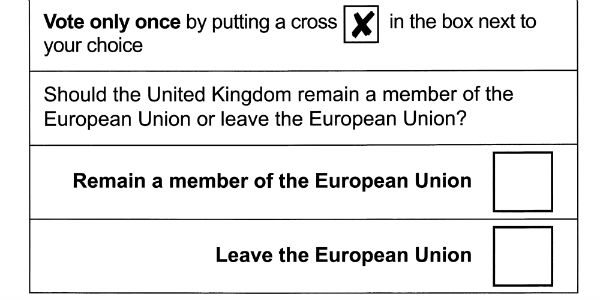

So (with some irony) while the merits of multiple choice referendums are open to debate – and the risks of apathy, fatigue, and confusion must be weighed against the divisive nature and limited scope of binary referendums – a multiple choice reworking of the EU referendum question might have better expressed the full spectrum of public opinion, from integration to separation. Consider this: on 23 June, would you rather have answered the question that appeared on the ballot paper, or this one?

How should the UK’s relationship with the EU proceed?

- Remain; further EU integration

- Remain; maintain current relations

- Remain; renegotiate a new deal within the EU

- Leave; join European Economic Area

- Leave; don’t join European Economic Area

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Lily Blake is studying philosophy and politics at the University of Bristol.

Lily Blake is studying philosophy and politics at the University of Bristol.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like? https://t.co/5k7OG9UfZz

This post addresses an important concept. We should support moves

to include it in a “Confirmation Referendum” on EU membership. However “open” questions are NOT conducive to the referendum

methodology.

The June 23rd question, with hindsight (!) should have been framed

as “Should the UK government take steps to negotiate withdrawal

by the UK from the Economic Union?” (Yes/No). That would have

avoided the claim by many on the Leave side that June 23rd was

the FINAL say on the matter.

What is needed now is serious thought about the question to be

posed in a “Confirmation Referendum” (which the precedent of

Greenland suggests ought to be held). ESSENTIAL in that will be

the use of “Preference Voting” (as in AV mentioned).

An initial draft would be to ask the electorate to rate the following

four options in preference sequence.

a) Leave the EU on the terms in the draft treaty.

b) Leave the EU unconditionally (ie on WTO terms)

c) Remain in the EU on February 2016 terms.

d) Request a further two years negotiating time.

Voters would use 1,2,3,4 to indicate preferences.

==

Of course implementing this is not in the gift of the UK government.

We need BEFORE triggering of Article-50, “talks about talks”.

Central to those would be agreement by the #EU27 to abide by

the result of such a referendum – including acceptance of the

withdrawal of the Article-50 request and a binding statement

by all twenty-seven that talks can be extended if such is the

outcome of the 2018 referendum.

These conditions (for talks about talks) should be included as

amendments to the “Article-50” bill proposed for early 2017 – so

that the current de-facto position does not apply (ie that the mere

triggering of Article-50 leaves no option but to leave two years

later – either with or without a suitable treaty).

The author of this piece has correctly identified that no-one really

knows the terms on which leave voters wanted to leave. It is now up

to the UK government to negotiate the best terms and then for the

people to decide on the basis of FACTS (ie the treaty terms) whether

or not to confirm a wish to leave. Individual electors will have all sorts

of concerns but these cannot be put as direct questions (eg the

options for the EU/Gibraltar border – very important for some but

not relevant for most).

Using preference voting is essential in all multiple choice ballots –

so that the voters can decide which majority grouping to join (the

groups being decided by the support given to each option).

For example, some of those wishing for an extension may wish

to leave if no solution emerges whereas others may wish to avoid

leaving if particular issues cannot be resolved.

How do we open up debate on this issue?

Time is of the essence.

We MUST have agreement before Article-50 is triggered – not

on substance but on the procedures.

Given that barely anyone actually knows what the EEA is, and even supposed ‘experts’ in the media cannot get it right, then you would have an uphill struggle getting any sensible response to a referendum question two of whose questions hinged on it. Most would think it is a spelling mistake for EEC (and that indeed is what happened when I was involved a decade ago and we wrote to 30,000 people who actually had a view on the EU and had expressed it to us).

One appreciates the sadness and sense of mourning felt by those who lost but it is really time to move on and try to get the best possible departure from the EU. To mess around with systems so as to simply ensure a ‘better” result is like the EU when it ordered Ireland to repeatedly hold referenda under slightly different premises until the voters gave the ‘right’ answer.

Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like? #EUref #Brexit https://t.co/80wKs9J5pf

Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like? via @democraticaudit

#Brexit #EUref2

https://t.co/boURecysdo

Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like? – Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/qreIOPKLn4

A multiple choice referendum of the sort described would seem to create more problems than it solves. You could have something like 72% backing some form of Remain (24% for each of the three Remain options), but then get 28% for Hard Brexit. Thus, the plurality winner is something opposed by a significant majority of the voters.

Of course, there are other voting systems, including AV, that might alleviate this particular difficulty – but, as the author mentions, the UK electorate rejected AV in 2011 (though this was NOT about proportional representation).

Another option might be to have multiple binary questions. For instance, there could be Q1 ‘in or out?’ and Q2 ‘if out, hard or soft?’ But even there, this creates a dilemma for someone who might favour Soft Brexit > Remain > Hard Brexit. They will have a clear answer to Q2, but not be able to answer Q1 easily without knowing the likely form that Brexit would take.

Thanks for engaging with the content of my article. I found your comments useful in developing my thoughts on this topic. There is certainly a big risk of making the problem worse by diving into using multiple choice referendums without thinking. I also think that the voting system used is key in avoiding the problem you describe.

A system such as STV might be useful in the instance of a multiple choice EU referendum. It is proportional and allows voters to rank the options in order of preference. The outcome ought to be an option that a plurality and majority would rank highly – either 1st or 2nd. The advantage of STV over AV is that the voter can place a ranking by every option, so if loads of people report that they are particularly opposed to ‘Hard Brexit’ and another particularly large number of people report that they are particularly opposed to ‘Further Integration’, it is clear that both of those extremes are deeply divisive and unpopular among many.

There are different ways of counting STV, and each would need to be considered for its own merits and issues. I suspect that, in general, this method would just lead to the moderate, or near moderate, option being chosen in most cases – whether this is a positive or negative effect is down to personal opinion. I think it would avoid divisiveness, but it might also be seen as anti-radical.

The notion of multiple binary Qs is interesting and potentially useful, though it might veer too much towards confusing and tedious for the voter. The New Zealand electoral reform of the 1990s was decided upon by votes on 3 separate questions and might be insightful. https://www.nzhistory.net.nz/politics/fpp-to-mmp/putting-it-to-the-vote

Given how AV was received in 2011, I’m not sure any ranking system would be popular. Further, there are dangers of arbitrariness and manipulability.

Perhaps a multiple option referendum combined with Approval Voting would work. Voters wouldn’t need to order their preferences, but could indicate which they did and did not find acceptable.

…and what does “Remain: maintain current relations” actually mean? How is that possible in the ratchet effect where the Eu is moving by its own admission to ever greater union? Does this mean no further rules, regulations, orders, Directives will be applicable? How to campaign on that when it is a fraudulent concept to campaign on? It is specifically not on offer from the EU. That’s why we had the referendum in the first place. The Electoral Commission would have a few words to say about a referendum offering things that are impossible. The first one (further EU integration) is the only possible one to offer of those two as it is the only thing on offer from the EU.

Beyond the binary: what might a multiple-choice EU referendum have looked like? https://t.co/A0TtYdoihE https://t.co/2E8FTAPoU0