Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden

Some Swedish local authorities have embraced online services and forms of digital democracy. Others have been slow to take up the opportunity. Gustav Lidén rates the country’s 290 municipalities according to the depth of their digital engagement, and looks at the possible factors influencing it. Lack of enthusiasm from senior politicians and bureaucratic inertia are key reasons why local councils are reluctant to invest in digital politics.

Detail of an expressionist mural by Axel Törneman depicting the building of Stockholm City Hall, 1925. Photo: George Rex via a CC-BY-SA 2.0 licence

Although a great deal of political and government activity now takes place online, there is no comprehensive understanding of why some local authorities’ online services are so much better than others. Significant variations exist when it comes to the opportunities for digital engagement (see e.g. Åström et al., 2012) even within otherwise fully democratic states (Reddick & Norris, 2013). In a recent study, published in Policy and Internet, I identify patterns and explore the differences between municipal websites in Sweden. For the purposes of this post, I refer to the existence of digital channels (such as the ability to perform tasks via municipal websites and usage of social media) that enable people to engage in local politics.

Exploring and mapping digital politics in Sweden

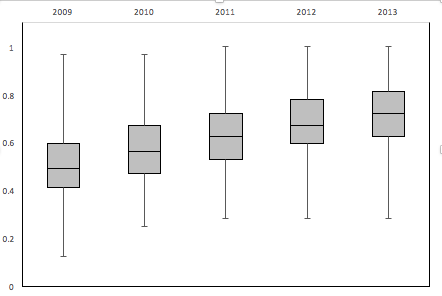

Using data from an annual content analysis of the functions of their websites, I created an index (ranging from 0.0 to 1.0) for Sweden’s 290 municipalities, based on identifying the features necessary for the practice of digital politics. This makes it possible to see whether the websites enable people to find the information they want and also (to a lesser extent) engage with local representatives. In total, I identified 32 of these functions – for example, minutes of council meetings, contact information for politicians and live-streaming of council meetings.

As the boxplot below shows, digital features have tended to increase year on year, although the growth rate has diminished in recent years. At the same time, provision is notably polarised. For example, the lowest value in the distribution did not increase between 2011 to 2013. In addition, a significant proportion of Swedish municipalities have scored low at least since 2010. In the light of rapid technological development and the fact that the index measures the same factors in 2009 as in 2013, this must be regarded as quite surprising.

Through regression analysis, the findings show that population size has the strongest effect on the index. Larger municipalities are more inclined to provide local websites with the features necessary for the practice of digital politics. Better-off municipalities also offered more online services. Furthermore, in some years the level of local people’s education has a positive effect on provision. This could suggest citizen-driven developments. However, this effect is diminishing over time, possibly because access to technology spreads from social elites to the wider population. However, the level of internet access among the local population had no effect.

A qualitative look at digital politics

These quantitative findings are accompanied by case studies which examine two municipalities struggling with digital politics. They report lower values on the applied index than those which would be expected from statistical modelling. Material was collected through interviews in each municipality, including the chair of the municipal executive board, leading opposition politicians as well as public officials. Theoretically, I made two assumptions about agency behaviour. First, politicians are expected to oppose the development of digital politics (Mahrer & Krimmer, 2005) because increased transparency and new forms of politics could ultimately put their own power at risk. Second, public officials are assumed to support the development of digital politics. This could both be due to the fact that public officials are inclined to work as community builders (Nalbandian, 1999) and that they saw the potential for digitalisation to strengthen discretion and autonomy for bureaucrats (Buffat, 2015).

The case studies confirmed that, with just one exception, no leading politician has shown enthusiasm for digital politics. Particularly striking is that even if one of the leading politicians in one of the studied municipalities was highly engaged in these matter, it was not enough to make significant advances. Although the motives for these standpoints have been hard to unravel, the general impression is of a lack of interest in working with these issues. Moreover, the behaviour of public officials is in no way self-evident. The findings indicate a fairly motivated administration that keeps the system working, but hesitates to do more without funding. It would be difficult to argue that the administration has taken on the role of community builder by embracing online services. This creates an environment which does not promote digital politics. Neither municipality had a long-term digital plan. One interpretation would be that this has neither been called for by the political leadership, nor prioritised by the administration.

Conclusions

The availability of digital politics rose in Swedish municipalities during this time period. But the availability of online services and opportunities to engage in local politics varies greatly in different parts of the country. In general, structural conditions will limit the possibilities and ambitions of local stakeholders. Certainly in Sweden, but plausibly also elsewhere, a number of preconditions have to be met before digital politics can take off. The right conditions and motivated and committed actors are important. Future research could seek to establish exactly what conditions are required.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit.

Gustav Lidén is Associate Professor in Political Science at Mid Sweden University, Sweden. His research on digital politics focuses on local democracy.

Gustav Lidén is Associate Professor in Political Science at Mid Sweden University, Sweden. His research on digital politics focuses on local democracy.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden https://t.co/BvGg49bRjU #localgov

Insights from #Swedem about what sorts of tech can help #LocalGov via @democraticaudit https://t.co/pw9uZL3JFA

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden: https://t.co/y01WPF5XzR via @democraticaudit #DigitalEngagement

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden https://t.co/fM4IntMi99

See my post in @democraticaudit on digital democracy at the local level in Sweden https://t.co/gO1BBDhFrO

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden https://t.co/HRgqZJSBiJ

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden https://t.co/mDdjYKVopt

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? @gustav_liden examines what makes the difference https://t.co/Suag89RlUX

Why do some local authorities have such poor websites? Insights from Sweden https://t.co/Suag89RlUX https://t.co/Q3LfEnAzbT