Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a ‘policy entrepreneur’

Political actors need to be nimble and respond to the opportunity to reform old policies and initiate new ones. Manuele Citi and Mogens K Justesen look at how the European Commission takes advantage of politically opportune moments (the ‘gridlock interval’) in the European Parliament to put forward new legislation. As a ‘policy entrepreneur’, it is therefore able to navigate European institutions and bring about change.

Vice-President of the European Commission Federica Mogherini and Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, talk just before a Council meeting in October 2016. Photo: European Council via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

One of the key roles of a democratic political system is to enable governments to adapt old policies and develop new ones as circumstances change. This is particularly true in an increasingly globalised world, where the fast pace of economic, social and demographic change put existing policies under pressure, making them rapidly obsolete or ineffective. The failure of European governments and the EU to address the current immigration crisis is a case in point.

But what are the key factors that determine policy reform? Political scientists have developed a variety of explanations that emphasise institutional constraints, the diffusion of new policy ideas, and the political ideology of governments. However, the political science literature generally highlights two factors that systematically affect the prospects of policy reform.

The first factor is the ideological position of key legislative actors (e.g., the Parliament and President) vis-à-vis the status quo. The farther veto players are from the status quo, the more likely they are to push for change.

The second factor is the ideological distance between the key legislative actors. When key actors are far apart ideologically, agreement on policy reform is difficult and gridlock tends to ensue. (This has been a problem in the US Senate, for instance.) When political actors are ideologically closer, compromise and policy change are likely. These are the central points of both George Tsebelis’ veto player theory, and Keith Krehbiel’s pivot theory, which have become the centrepieces of analysis of policy stability and change.

Another factor often mentioned in the media and scholarly literature is the role of the ‘policy entrepreneur’. A policy entrepreneur can broadly be defined as a political actor who – based on ideas or interests – initiates and promotes policy change. While policy entrepreneurs may have a fundamental role in doing this, the relationship between political constraints – represented by the distance between veto players – and the level of legislative activity of policy entrepreneurs is still largely unexplored in empirical political science.

Whether motivated by ideas or interests, policy entrepreneurs may be sensitive to the institutional environment they operate within and step up their activities when the ‘political opportunity space’ widens – for instance, when veto players get ideologically closer to each other. This, in turn, may also result in increased legislative activity and more extensive policy reforms.

How it works in the European Union

In a paper published recently in the European Journal of Political Research, we examine this relationship between the institutional opportunity space, legislative activity, and policy change in the context of the European Union – a legislative system characterised by two formal veto players: the Council and the European Parliament. These two legislative branches are populated with actors with specific political affiliations. However, what really matters when it comes to passing legislation is the position of the ‘pivotal voter’, i.e. the legislative actor whose consent is necessary to pass legislation.

On a left–right scale, the pivotal voter in the European Parliament is the median voter – or the party that occupies the median position – whereas in the Council it is the member state that can tilt the qualified majority to one side or the other. This means that the opportunity space for policy change has an inverse relationship with the inter-cameral distance between the two pivotal actors (called the gridlock interval). The smaller the distance between the pivotal actors in the Council and the Parliament, the larger the political opportunity space for policy change, and vice versa.

But who plays the role of policy entrepreneur in the EU? This is where the European Commission comes into play. Given that the Commission has the exclusive right to initiate legislation, the Commission is the EU’s central policy entrepreneur. However, the Commission’s level of legislative activity varies, resulting in higher (or lower) volumes of legislative initiatives at various points in time.

In our empirical analysis, we examine the links between the political opportunity space, the Commission’s legislative activity, and policy change. First, we analyse how the Commission alters its legislative activity in response to changes in the political opportunity space. Second, we examine whether the Commission’s choice between stepping up or scaling down legislative initiatives translates into more extensive policy reforms – approved by the two legislative chambers of the EU. Our results suggest that the Commission’s policy entrepreneurship is affected by the political opportunity space and that this has implications for the scale of policy reform in the EU.

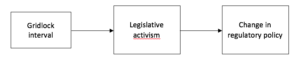

We use panel data for eight policy sectors in the EU – related to the utilities and transport sectors – observed over nearly 30 years, and are analysed using so-called negative binomial regressions with sector fixed effects. The data – which build on our earlier work – incorporates information on three variables that are key to our analysis. First, to measure policy change we use data on regulatory change across the eight sectors. Second, as a proxy for the legislative activism of the EU’s key policy entrepreneur – the Commission – we use data on the yearly number of legislative proposals on a sector-by-sector basis. Finally, to measure the political opportunity space, we use data on the gridlock interval developed by Crombez and Hix. The relationship we examine can be portrayed in the figure below.

Source: Citi & Justesen 2016

The results of the empirical analysis corroborate our two main expectations. First, when the gridlock interval narrows – and the political opportunity space widens as a result of more homogenous policy preferences among pivotal legislative actors – the Commission steps up its legislative activity. This suggests that the Commission keeps a keen eye on the political situation in EU’s legislative branches and increases its volume of legislative proposals when it is strategically opportune to do so. Second, our results also show that – by increasing the volume of legislative proposals – the Commission is, in fact, successful in generating significant policy change (at least in the case of policies regulating key sectors of the internal market). By doing so, the Commission is instrumental in bringing about more policy change within the EU.

These findings suggest not only that legislative institutions matter for policy change, but also that policy entrepreneurs seeking to promote policy change can navigate successfully and adopt their strategies to changes in the institutional and political environment. When policy entrepreneurs find themselves in privileged positions – as in the case of the European Commission – they are highly instrumental in enacting policy change and can use that privileged position to push for policy change, particularly when political conditions are favourable.

References

Citi, Manuele and Mogens K. Justesen. 2016. ‘Institutional constraints, legislative activism, and policy change: The case of the European Union’, European Journal of Political Research 55(3), 609-625.

Citi, Manuele and Mogens K. Justesen. 2014. ‘Measuring and explaining regulatory reform in the EU: A time-series analysis of eight sectors’, European Journal of Political Research 53(4), 709-726.

Crombez, Christophe and Simon Hix. 2015. ‘Legislative Activity and Gridlock in the European Union’. British Journal of Political Science 45(3), 477–499.

Krehbiel, Keith. 1998. Pivotal Politics: A Theory of U.S. Lawmaking. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press.

Tsebelis, George. 2002. Veto Players: How Political Institutions Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Manuele Citi and Mogens K Justesen are Associate Professors in the Department of Business and Politics at Copenhagen Business School.

Manuele Citi and Mogens K Justesen are Associate Professors in the Department of Business and Politics at Copenhagen Business School.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

.@crombez & @simonjhix BJPolS paper referenced on @democraticaudit – https://t.co/oa2zRuh5q1

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a ‘policy entrepreneur’ https://t.co/gLjSf1Kx30

Blog post at @democraticaudit on policy change in the #EU with @manueleciti based on our recent @EJPRjournal paper https://t.co/vdLFmHswy8

.@manueleciti & @mkjustesen on the role of @EU_Commission as a policy entrepreneur

https://t.co/Pxe5ezpmxh

See also: #CCCTB, #ATAD, #pCBCR

A blog post I just wrote with @mkjustesen: how the EU Commission seizes political opportunity for policy change. https://t.co/ub7nByHyxW

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a ‘policy entrepreneur’ https://t.co/SGy8ObO1kW

#AffiliateMarketing

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a #affiliatemarketing https://t.co/jnnhP9uxTF …

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a #affiliatemarketing https://t.co/px3IHAP0f0 https://t.co/GTl3ZQwlLN

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a ‘policy entrepreneur’ https://t.co/SGy8Oc5CJw

Seizing political opportunity: how the European Commission becomes a ‘policy entrepreneur’ https://t.co/4CQISPNUnm https://t.co/eZZkGvE5L7