The Decline of Policy Mandates in Australia

Ruling parties often make reference to having a ‘mandate from the people’ for their actions, but refrain from mentioning this concept while in opposition. Ross Stitt analyses data showing that less and less Australian voters are participating in primary elections. As the primary vote of incoming governments declines, so too does the level of any potential policy endorsement and hence the legitimacy of any claim to a policy mandate. Under such circumstances, politicians should rather refrain from any mention of mandates, he argues.

Parliament House Canberra, Australia. Credits: JJ Harrison (CC BY-SA 3.0)

Perhaps there is no term more misused and abused in Australian politics than ‘mandate’. When in government both the Coalition and the Labor Party insist that they have a mandate ‘from the people’, but behave as if there is no such concept when in opposition. If there was ever any doubt about the cynical reality, it was put to rest in the National Press Club Leaders Debate during our most recent election. The moderator Chris Uhlmann asked the Prime Minister and the Opposition Leader to confirm that their opponent would have a mandate on health issues and company tax cuts, respectively, if they won the election – ‘Can you each agree this evening that at least on those things … the other side will have a mandate if it wins’. Their responses were as obfuscatory as they were unsurprising, and neither party was prepared to accept that the other could have a mandate. Now that the Coalition has been returned to government with a wafer thin majority, the claims and counterclaims over various mandates have begun and will play out over the course of this parliament.

Mandate theory contemplates that competing political parties present alternative policy platforms to the electorate, the electorate elects the party whose platform it favours, and then that party implements its platform (Judge, 1998, p. 71). A mandate incorporates both an obligation on the government to implement and some kind of ‘right’ to do so bestowed by voters. However, there is no legal or formal constitutional basis for that right. At best it arises by convention.

Ultimately, the democratic legitimacy of a government mandate to implement policies can only come from the effective endorsement of those policies by voters through the electoral process. That endorsement factor is implicit in the way that politicians employ the mandate concept. For example, before the last election the Cabinet Secretary, Arthur Sinodinos, said that a Coalition government would get its proposed superannuation reforms through Parliament ‘once people see the changes to superannuation in their totality, and we get a mandate from the public to implement them’. The implication was that, by electing a Coalition government, the public would be endorsing the Coalition’s superannuation policies. (Ironically some of the Coalition’s own MPs are now seeking to deviate from that mandate, even if it means crossing the floor in Parliament.)

However, the endorsement by the public of an elected government’s policies is not really a valid assumption. Strictly speaking, true endorsement can only occur when the following conditions, inter alia, are satisfied.

- Voters vote prospectively not retrospectively.

- Competing parties offer policy choices to voters.

- Voters are informed about policy choices.

- Voters ‘policy vote’ on the basis of party policies rather than other factors such as historical loyalties or the personalities of individual politicians.

- The government is elected with a majority of votes.

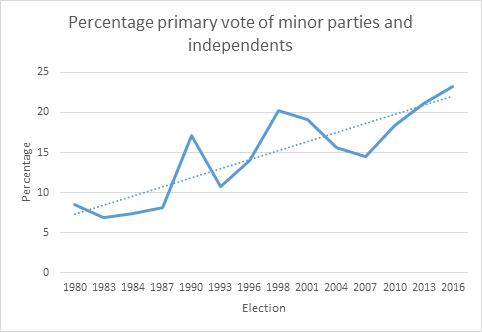

Reading that list, it quickly becomes apparent that in practice policy endorsement is an unlikely basis for any valid mandate claim in Australian federal politics. Condition (e) is particularly problematic given the preferential voting system for the House of Representatives and the growing proportion of voters who do not give their primary vote to either the Labor Party or the Coalition, the only viable contenders for the government benches. It is the primary vote that best reflects a voter’s personal policy preferences; the vote that constitutes a true policy endorsement. The graph below records the percentage of the primary vote won by minor parties and independents in the last fourteen elections.

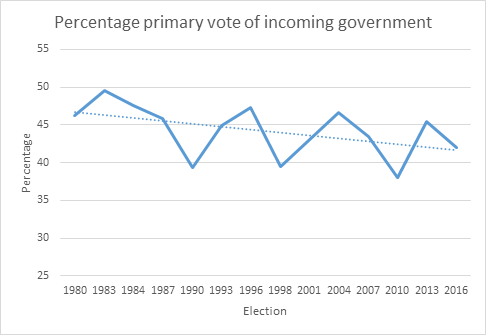

The trend is unmistakable. An increasingly smaller proportion of voters are giving their primary votes, and hence their primary policy endorsement, to the two major parties. This is reflected, inevitably, in the long term decline in the primary vote won by the incoming government, as illustrated below.

As the primary vote of incoming governments declines, so too does the level of any potential policy endorsement and hence the legitimacy of any claim to a policy mandate based on such endorsement. It is also worth noting that data from the Australian Election Studies surveys show that many voters for the winning party in federal elections locate their own views on a range of policy domains closer to the policies of the alternative government. In other words, even those who vote for the incoming government should not be taken as endorsing all its policies.

Policy mandate claims are increasingly difficult to justify on electoral endorsement grounds. Furthermore, they do not appear to have the consistent support of either the Coalition or Labor and, absent that support, it is not obvious how the minor parties and independents can reasonably be expected to observe them. Under the circumstances, politicians might be better off refraining from all mention of mandates. That would be consistent with the view expressed by the last leader to win more than one election, John Howard – ‘The mandate theory of politics from the point of view of proper analysis has always been absolutely phoney’.

—

This post was originally published at Pop Politics Aus / The Policy Space and is here republished with permission. The article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Democratic Audit blog, or of the LSE.

—

Ross Stitt is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The Decline of Policy Mandates in Australia https://t.co/5YE6a8U2Ln

The Decline of Policy Mandates in Australia https://t.co/n9t3hMHV6Z

The Decline of Policy Mandates in Australia https://t.co/rDrVAMTVVN https://t.co/K9tsHWTRKz