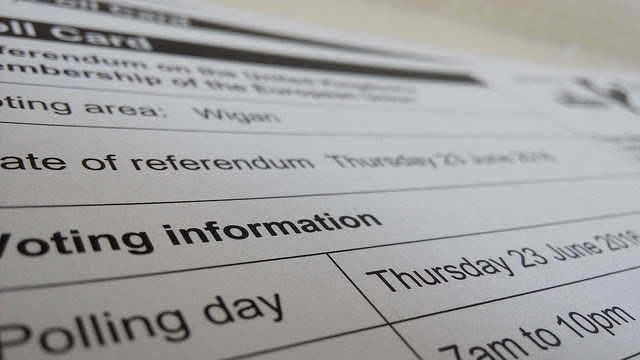

The Brexit referendum is upon us, with the contest on something of a knife-edge according to polling. Here, Simon Wren-Lewis looks at the way the debate interacts with notions of democracy, arguing that policymakers need to find acceptable arrangements that partially limit each element of the ‘trilemma’ which posits the impossibility of simultaneously enjoying national sovereignty, hyper globalisation, and democracy’.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard

writes eloquently and honestly about why he will be voting for the UK to leave the EU. Honestly because he gives chapter and verse on how “anybody who claims that Britain can lightly disengage after 43 years enmeshed in EU affairs is a charlatan or a dreamer.” His argument to nevertheless Leave is straightforward:

“it comes down to an elemental choice: whether to restore the full self-government of this nation, or to continue living under a higher supranational regime, ruled by a European Council that we do not elect in any meaningful sense, and that the British people can never remove, even when it persists in error.”

Although he does attack the Commission “with quasi-executive powers that operates more like the priesthood of the 13th Century papacy than a modern civil service”, and although he talks about the European Court of Justice on which I have no expertise, most words are spent denouncing those that created the Euro, and here I have some knowledge. He writes

“Nobody has ever been held to account for the design faults and hubris of the euro, or for the monetary and fiscal contraction that turned recession into depression, and led to levels of youth unemployment across a large arc of Europe that nobody would have thought possible or tolerable in a modern civilized society. … We do not know who exactly was responsible for anything because power was exercised through a shadowy interplay of elites in Berlin, Frankfurt, Brussels, and Paris, and still is.”

Is this really the case? We know that the push for a monetary union came from France in particular. Germany was less enthusiastic, and therefore demanded as a price some central control of national budgets because they feared that a profligate government could cause systemic problems. When those fears proved correct, they doubled down on that central control and also believed a union wide demonstration of austerity was required. I strongly disagree with all of this, and have thought a lot about why it happened, but a lack of democracy is not high on my list of culprits. After all the Eurozone did

not cause austerity to happen in the UK and US.

The fact that democracy was overridden in Greece so cruelly was not the result of actions of unelected bureaucrats, but of elected finance ministers from the other union countries. One reason these finance ministers refused to write off any debt was because of pressure from their own electorates. This exercise in raw political power worked because the Greek people wanted to stay in the Euro. The ‘bad equilibrium’ Evans-Pritchard talks about happens in part because of democracy. The lesson I would draw is that union governments should not lend money directly to other union governments, precisely because governments are democratic and so find it hard to accept write-offs.

Dani Rodrik

talks about an impossible trilemma: how you cannot have all three of ‘hyper globalisation’, national sovereignty and democracy. The key question is whether you can find acceptable arrangements that partially limit each of these rather than abandoning one altogether. That is a tricky issue of design, and it is clear that the Eurozone has not succeeded so far. Too many assume that this failure condemns all attempts at monetary union, and that the only way forward is full political union. If that is what is meant by saying there is no chance of a democratic Europe anytime soon I agree, but I think that form of democracy was

always a step too far too soon.

There is no shortage of ideas of how the Eurozone could be improved that fall well short of political union. It is simply not the case that you can only have one monetary union design, so you cannot reject the whole concept based on one failed experiment. It is quite possible that in the short term Germany or others may block reform, but it is far from obvious why Germany or others should prevent reform in the longer term. Germany does not want to repeat what happened in Greece.

Above all this, there is a fundamental point. The Eurozone as it currently stands is not immutable, or inevitably

dying, or some kind of monster that is bound to ensnare the UK or bring it down. If the Eurozone did become one of these things, we can always exercise our option to leave. In contrast, once we leave, it will be a long time before we can change our minds.

—

This post also appears on Simon Wren-Lewis’s ‘Mainly Macro’ blog. It represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Simon Wren-Lewis is Professor of Economic Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government, Oxford University, and a fellow of Merton College. This blog is written for both economists and non-economists.

Similar Posts

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Success of European project rests on the ability to balance ‘hyper globalisation’, national sovereignty & democracy https://t.co/I5prJQaR8D

The success of European project rests on ability to balance hyper #globalisation, #nationalsovereignty & #democracy https://t.co/aCBknKxNes

The European project ‘s success depends on balancing ‘hyper globalisation’, national sovereignty, and democracy https://t.co/F60ZkEg1yp

In your article you claim that : “UK or bring it down. If the Eurozone did become one of these things, we can always exercise our option to leave. In contrast, once we leave, it will be a long time before we can change our minds.”

Can you explain how that can be achieved if we choose to remain in the EU following legislation proposed in the 5 Presidents report and David Cameron having to give up give up one of Britain’s few remaining vetos, Britain’s right to give or withhold consent to future treaties which convert the Eurozone block into a European Superstate in order to agree a “Red Card” for the UK. Providing we can get 14 other members states to agree.

The success of European project rests on ability to balance ‘hyper globalisation’, national sovereignty, & democracy https://t.co/uFgPeUuhCy

Success for the European project depends on balancing ‘hyper globalisation’, national sovereignty, and democracy https://t.co/F60ZkDYqGR

The success of the European project rests on the ability to balance ‘hyper globalisation’,… https://t.co/uhPMMRQbWl https://t.co/Ly6RmAPXWY