Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too

Less than a year after the election, average polls suggest that Labour continue to poll at about the same level or worse than the 2015 result. Anthony McDonnell writes that this is worrying for the Left, as previous trends indicate their poll numbers usually rise significantly relative to the Conservatives’ within months of the Tories taking office. He argues that if Labour doesn’t widen its lead in the polls now, mobilising new voters alone will not be enough to win the 2020 general election.

Credit: Jason CC BY-NC 2.0

I recently came across a Conservative Party ad in the Evening Standard stating that you shouldn’t vote for “Corbyn’s man” in the London Mayoral elections. This made me curious: Labour are only polling a couple of points behind the Tories, so is the “Corbyn is a vote loser” line actually true, or does this narrative continue to be a fiction created by centrist and right wing media and politicians to undermine the new Labour leader? To answer this question I compared his polling numbers to that of his predecessors polling data and see how Labour normally fare nine months after an election.

Between 1979 and 2010 the Conservative Party won five general elections (where it was the largest party and formed a government). Drawing on data from Labour’s time in opposition during these periods it is possible to see how well it has polled since the general election last May. General election results were taken from the BBC and opinion poll data was obtained from UK Polling Report.

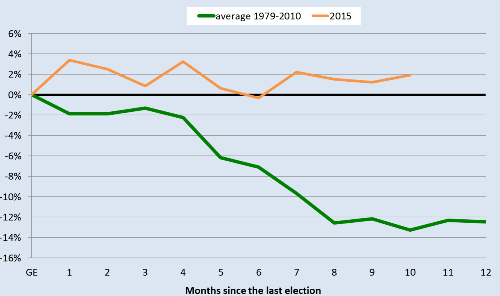

After every election victory between 1979 and 2010 the Conservative poll numbers started to drop significantly relative to Labour’s within months as is shown in the graph below. The pattern suggests that on average you’d expect a Conservative government to lose 12.5% of the electorate in its first year, with four of the five governments facing a reduction in support that is greater than 10% (1987 was the exception and the only year Labour didn’t change leader).

Figure 1: Change in Conservative support since last election

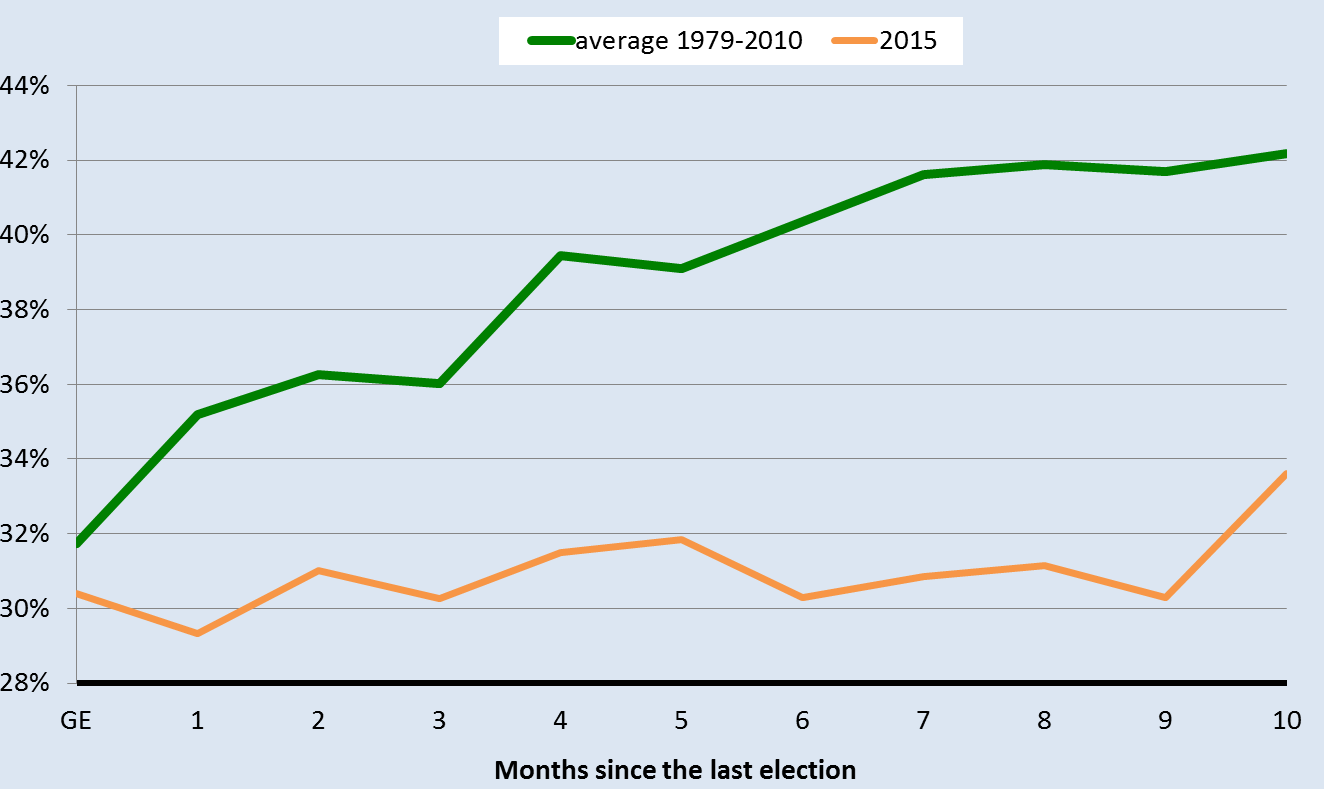

Nine months after the 2010 election Labour was polling 13% better against the Tories than they’d done in the election, and had a 6% lead overall. After 1992 they’d improved their polls by 13.5% and in earlier elections the increase was 8%, 13.5% and 15.5% for 1987, 1983 and 1979 respectively. In February 2016, nine months after the election, average polls suggest that Labour continue to poll at about the same level or worse than the 2015 result, and lower than they were polling just before the election.

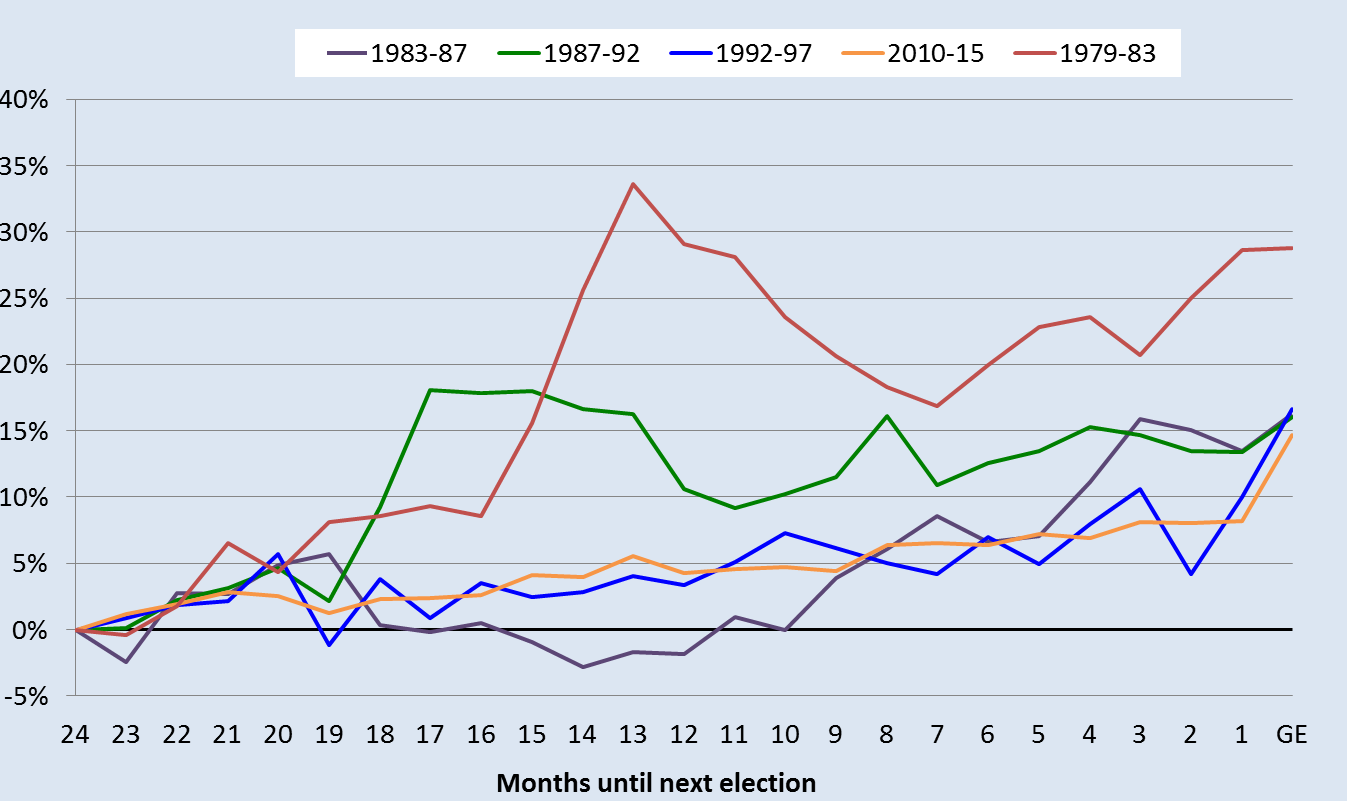

Figure 2: Labour Party polling in months after election defeat

This should be worrying for Labour supporters, because as well as losing large amounts of support after every election, during their previous stints in government the Conservatives have also won back large amounts of support in the two years prior to an election with an average gain of 18.5% against Labour. Even in 1997 when Labour won an “historic landslide”, the Conservative won back 16.5% of the electorate in the final two years of the parliament. Labour’s victory thus seems less based on the election campaign itself, and more on the fact they opened up a significant lead during the early to middle part of the parliament, a gap that was simply too large for the Conservatives to close.

Figure 3: Change in Conservative support before an election

During Corbyn’s campaign to lead the Labour party, many of those who opposed Corbyn stated that they did not think he could win a general election. The counter argument that was put forward by the Corbyn campaign was that while the new leader might struggle to convince Conservative and Liberal Democrat voters in the way that Blair did, he can win the election by bringing more people to the polls. In August he argued that he could win the next election by “expanding the electorate.” Corbyn successfully attracted people into the Labour party for his election, and there were more people who didn’t vote at all than Conservative voters in 2015, so at a glance this seems like a powerful argument.

However, on closer inspection several factors make it less persuasive. First of all, a disproportionate amount of the people who stay at home are in constituencies that the Labour party has already won, with turnout in these seats at 62% against the 69% in Conservative held seats. Secondly while it might sound like a significant number of people didn’t vote, at 66.1% turnout in the last election was at its highest for 18 years. Thirdly and most crucially, Labour were a long way short of a majority in 2015 and to get those votes from an increased turnout would be difficult. The impact of an additional voter is lower than a converted one. In a Conservative-Labour marginal, Labour will gain the same amount from convincing 5 former Tories to vote for them as they gain from convincing 10 people who otherwise have stayed home. This is because with converts they are both taking votes away from the Tories and increasing their own share.

To estimate what type of turnout would be necessary for a Labour victory, I modelled the 2020 election, and presumed that all voters who voted in 2015 will vote for the same party in 2020, with the same constituencies (in reality constituency boundaries might be less favourable for Labour). I then looked at what would happen if some of the people who stayed at home in 2015 could be convinced to vote for Labour, while the number of votes remained constant for other parties. I then increased turnout in proportion to the number of people who didn’t vote in each constituency. In order to get the most seats in Parliament in this scenario, Labour would need to convince 22.5% of the people who didn’t vote in 2015 to come out and vote from them in 2020. This would mean a turnout of 73.8%, the highest level since 1992, and well above the OECD average. To get a majority they’d need convince 35.2% of stay-at-homes to come out, requiring a 78.1% turnout. This would be the largest in 40 years. Even then, as Cameron is discovering, with a very small majority it can be difficult to get changes through the House of Commons, and Corbyn would probably be unlikely to be able to pass most of his radical reforms. To match their 2005 majority of 66 seats, Labour would need to increase turnout to 81.2%, a level not seen since 1951, and have all additional voters vote for them. It is worth noting that the last two scenarios rely on a greater proportion of non-voters to support Labour than their current poll numbers.

Given the difficulty winning a general election through increased turnout, Labour’s current inability to gain traction in the polls and the almost inevitable rise in the polls the Tories will get in the second half of the parliament, it seems unlikely that Labour will be returned to power, without a major change within the party, or an unrelated collapse in Conservative support.

While March was not a great month for the Conservative party, with large amounts of infighting around the EU referendum, an unpopular budget and doctors’ strikes, the last two published opinion polls still gave the Conservative Party a two point lead. It is also worth nothing that every Tory government analysed here went through quite intense periods of infighting, with the Prime Minister being forced out in 1990. However with the exception of 1997, all were able to reunify in the run up to next election and retain power, so a collapse in support remains unlikely without changes in Labour’s popularity too. Furthermore, Labour would be doing very well to catch up with their average when in opposition, but the fact that in four out of five of those cases they still went on to lose the general election would suggest they actually need to do much better than this average if they’re to be returned to power in 2020.

__

Note: This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Anthony McDonnell is head of economic research on the Independent review into antimicrobial resistance, chaired by Jim O’Neill. Prior to this he under took a master’s degree in public and economic policy at the London School of Economics where his dissertation examined electoral competition in UK local government. Previously Anthony worked as an assistant editor for LSE’s review of books blogs.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

[…] Note: This post was originally published on Democratic Audit UK. […]

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too https://t.co/cZii5BPjLT

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too https://t.co/MWWqGosC6G

https://t.co/r7HAVLjVH3

‘Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too’ – https://t.co/Z7GBUVMpWb

Or, alternatively, the Tories won back significant support in the run-up to previous General Elections PRECISELY BECAUSE they’d suffered such a significant loss to Labour during the immediate 12 months following the previous Election. Thus a large pool of former Tory voters (now very weakly-aligned to Labour) were just sitting there waiting to be won back by the Tories.

Which would mean = major post-Election Tory-to-Labour swing results in major Labour-to-Tory swing before next Election.

Equally, a MINOR post-Election Tory-to-Labour swing (as in 2015-16) results in only a MINOR swing back to Cons before next Election.

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not without winning over Tories. https://t.co/E7h0juRnY9

https://t.co/3qjEeRJ8dd Interesting article about how catastrophically bad the 2020 election will be for @UKLabour under Jeremy Corbyn

RT @ProfTimBale: Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too https://t.co…

RT @gsoh31: Good on pernicious non-voter myth that you still sometimes hear on Left, despite fact it’s been totally debunked.

https://t.co/…

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too https://t.co/AVNX4CildP

Apologies, but the model assumptions are poor/uninformative. No model runs that allow for vote switching? And where is the methodology?

Notable that 2016 polling absent from all graphs.

Also notable that we don’t get a per election breakdown for Labour, while we do for the Conservatives. I would like to see what that looks like.

And why are the 2001 and 2005 results not shown for Conservative per election cycle breakdown?

Dear James,

Thank you for your comment. You are correct that it is a very simple model. The point was to show that without convincing people from other parties to vote for Labour they will struggle to win the election even with higher turnout and retaining all of their 2015 votes (which is how Corbynites have suggested he might win)

The first two graphs exclusively use data from 2015 and 2016 for the Orange line, so recent polls are represented, though as they were monthly estimates and the data work was done in March, only January and February are included, but March results are discussed in the final paragraph too.

The reason Labour government cycles are left out is that they tend to run quite differently. When in government Labour initially gain support after the 1997 election which in the years since regular polling has never happened to the Conservatives. They also lost support much more slowly over time rather than having big dips and with the exception of 2010 there was not a pro-government bounce in the months before the election. For this reason it did not seem sensible to use this data to analyse the current situation a Conservative government and Labour opposition.

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over Conservative supporters too https://t.co/9Mm4t7y1Vy

@democraticaudit Why bother with Tories? The People want real humanity and compassion, not reckless cruelty.

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? https://t.co/YltYy15Tgo

Could Corbyn win an election by mobilising non-voters? Not if he doesn’t win over… https://t.co/qCY7erlMKI https://t.co/fOUkupe0sv