The political potential of migrants is often overlooked in discussions around integration

In a recent study, Hanna Wass, Päivi Pirkkalainen and Marjukka Weide drew on the Somali community in Finland as a case study to consider immigrants as a political resource. They found that turnout among Somali-born voters was only slightly lower than native citizens, and that their engagement in civic associations is highly dynamic and diverse. The results demonstrate that political potential of immigrants is often overlooked and highlight that economic and social inclusion are closely intertwined with political inclusion.

Lining up for 2008 local elections in east Helsinki. Credit: Tammisto CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Europe is currently witnessing an increasing number of immigrants who are mostly asylum seekers from war-torn countries outside the EU. As a consequence, migration has become one of the top issues on the European political agenda, but it is also one of the most contested. In terms of accommodation of diversity and social inclusion, the contemporary European context faces several challenges. The societal atmosphere is characterised by growing xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiments, represented by populist and radical right parties and various actors in civil society. In public discussion on immigration, much attention is paid to security threats caused by immigrants, their vulnerability due to marginalisation, and to radicalisation as a possible outcome.

There are also more positive voices, emphasising the human rights of the newcomers, as well as those pointing out the economic potential of migration. According to the latter view, accelerated immigration could balance the dependency load in rapidly aging European societies. Yet, the current debate has almost completely disregarded immigration as a political resource. When political inclusion of newcomers is addressed, the perspective is usually a negative one, highlighting lower turnout among enfranchised immigrants, fewer mobilisation attempts by political parties and under-representation of new ethnic minorities among candidates and legislators.

Our recent study examining the Somalis in Finland takes notice of the often overlooked political potential among immigrants.[i] The Somali-speaking minority has around 16,000 members and is the most visible and widely known group with background in humanitarian migration. According to an EU-MIDIS report, it also experiences more ethnic discrimination than other foreign-born groups in Finland, such as Russians and Estonians.

We concentrated on two types of political participation, i.e. voting in municipal elections and activity in civic associations. The first analysis was based on individual-level data on turnout in the 2012 Finnish municipal elections. In Finland, foreign residents (other than Nordic and EU citizens) are entitled to vote and/or run as a candidate in municipal elections if they have a domicile in Finland continuously for two years and 51 days prior to an election. The data were compiled from those electoral wards that utilised electronic voter register (n=585,839). The data, administrated by the Ministry of Justice, were released to Statistics Finland after the elections. In Statistics Finland, the information on whether a person voted or not was linked to various indicators of the individual’s socioeconomic status and migration history with the help of personal identification numbers. Altogether, the data included 492 voters born in Somalia.

Our results show that turnout among Somali-born voters in the 2012 municipal elections, at 40%, was only slightly lower than among voters born in Sweden and clearly topped participation among Estonians and Russians. Interestingly, Somali men were fractionally more active voters compared to women (40% vs. 39%). This observation challenges stereotype of migrant women, often portrayed as more vulnerable and more politically passive than men of the same origin.

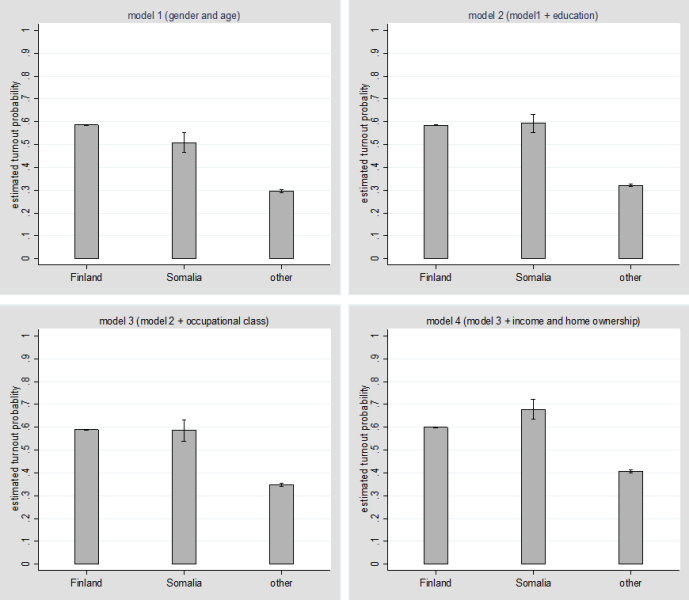

Electoral participation among Somali-born voters is, however, negatively influenced by their socioeconomic status, which is lower compared to native citizens and other foreign-born groups. Somalis often face difficulties in finding work, especially opportunities that would correspond to their level of education, which leads to lower level of income. In turn, economic hardship can limit both resources and motivation for political engagement as well as undermine the sense of political inclusion. As shown in Figure 1, when various indicators of socioeconomic status (education, occupational class, income and home ownership) are taken into account, voting propensity among Somali-born was actually higher than among native citizens.

Figure 1 Estimated turnout probability by country of origin in the 2012 Finnish municipal elections.

In scrutinising Somali’s involvement in civic associations, we used interview data which were gathered as a part of Päivi Pirkkalainen’s previous research. The results indicate that the organisational structure of associations is highly dynamic and diverse, ranging from activities related to supporting integration into the Finnish society, such as language courses and employment training, to leisure activities and children’s afternoon clubs.

The associations are often maintained by a handful of activists and their personal networks. Thus the associational field is in constant flux as some organisations are disbanded, for instance due to termination of project funding, while new ones are simultaneously formed. In addition to specific ethnic associations, many Somalis are active in native Finnish or multicultural organisations.

Somali-born voters constitute a reveling example of accumulating character of political engagement. Activity in ethnic and other types of organisations often increases institutional and social trust, which paves the way for political participation. It may also reduce experiences from discrimination, which is particularly important in the case of Somalis in Finland.

There are certain factors that contribute to political activity among Somali-born voters. Somali families have often several children. A previous study by Wass at al., based on the same individual-level register data from the 2012 Finnish municipal elections, shows that the parenthood of minor children increases voting propensity among foreign-born voters. This seems logical as regular contact with schools forms a social bond between the parents and the public institution, which may increase also trust in political institutions in new home country. Moreover, Somalis typically live the capital area and specific neighborhoods. As the studies conducted in the UK have demonstrated (Cutts et al. 2007; Sobolewska et al. 2013), regional concentration not only enhances the internal mobilisation among a certain ethnic group but also makes it more identifiable for parties as a potential constituency.

The implications of these findings are two-fold. First, they underline the political potential among newcomers that so far have remained largely latent. For instance, there are still relatively few foreign-born candidates running in elections and even fewer become elected. Depending on their own political identity and profile, such candidates can bring out issues meaningful for not only to ethnic minorities but native voters alike. Increased diversity on the political agenda would have positive democratic consequences by enhancing representativeness of the system.

Second, as our results demonstrate, economic and social inclusion are closely intertwined with political inclusion. The causal chain between these three, is however, not self-evident. Political engagement can enhance wider societal accumulation in several ways. It would be valuable to recognise this aspect in public discussion on migration and various integration programs.

__

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

__

Päivi Pirkkalainen is a post-doc researcher in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä. Her current research analyses the role of migrant youth organisations in the Finnish third sector. Her work has been published in journal such as Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Nordic Journal of African Studies and Finnish Journal on Civil Society.

Päivi Pirkkalainen is a post-doc researcher in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä. Her current research analyses the role of migrant youth organisations in the Finnish third sector. Her work has been published in journal such as Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, Nordic Journal of African Studies and Finnish Journal on Civil Society.

Hanna Wass is an academy research fellow and university lecturer in the Department of Political and Economic Studies at the University of Helsinki. Her current project “Equality in electoral participation and vote choice”, funded by the Academy of Finland, examines turnout and representation from various perspectives. She is a member of the steering committee for the Finnish National Election Study, and the co-convenor of the ECPR standing group “Public Opinion and Voting Behaviour in a Comparative Perspective”. Her work has been published in journals such as Electoral Studies, the European Journal of Political Research, Parliamentary Affairs and Political Research Quarterly. She is a co-author of the book “Health and political engagement”, forthcoming in Routledge in 2017.

Marjukka Weide is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä. She conducts her doctoral research as a part of the project “Superdemocracy: a critical assessment of the participative turn”, funded by the Academy of Finland.

Marjukka Weide is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy at the University of Jyväskylä. She conducts her doctoral research as a part of the project “Superdemocracy: a critical assessment of the participative turn”, funded by the Academy of Finland.

__

Note

[i] The original study is available only in Finnish.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

The political potential of migrants is often overlooked in discussions around integration https://t.co/MgSAawJQcv

https://t.co/zHbLhMuC8S Discussions on #immigration are often centred around #integration and overlook political potential of migrants

The political potential of migrants is often overlooked in discussions around integration https://t.co/qfdCc6rGOC

The political potential of migrants: The case of the Somali community in #Finland https://t.co/oZFhOMjzad

Migrants and political participation: important new findings from Finland discussed @democraticaudit https://t.co/ywZX3PKCYY

The political potential of migrants is often overlooked in discussions around integration https://t.co/jo6bxCLYSM

The political potential of migrants is often overlooked in discussions around integration https://t.co/xaTHMmResF https://t.co/cO9cYqDTfl