The blurring of party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of regulatory regimes

The way in which political parties use state resources indirectly (e.g., parliamentary expenses) receives substantial attention in public debate, particularly when surrounded by perceptions of misuse. Nicole Bolleyer looks at the different ways in which parliamentary resources are used in party-political ways, and argues that attempts to bring about reform will be limited by the reality on the ground.

Credit: Natesh Ramasamy, CC BY 2.0

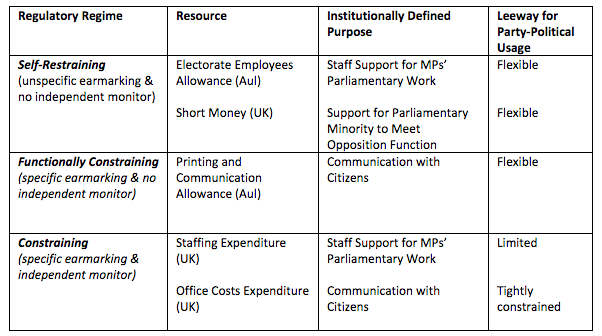

The way in which political parties access and use state resources attached to their institutional roles (e.g., expenses and staffing expenditures for MPs, subsidies for parliamentary groups) for party-political purposes tends to receive considerable attention in public debate, particularly when surrounded by perceptions of misuse. Yet little is known about how the usage of resources available to party representatives holding public office is regulated, to which extent vague regulation provides leeway for party-political usage or whether strict regulation effectively prevents the latter. Comparative research in the UK and Australia shows that regimes regulating the usage of resources vary considerably (within and across political systems):

a) in their specificity (i.e. the extent to which regulation explicitly defines ‘institutional usage’ and vice versa prohibits party-political or partisan usage) and

b) whether rule compliance is externally monitored by independent regulators.

It further suggests that the blurring of party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of regulatory regimes that democracies adopt, regardless of detail and external enforcement. Even when strict regulation is adopted as a response to a scandal (as in the aftermath of the UK expenses scandal which led to the creation not only of new constraining rules but also the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority (IPSA) as an independent regulator), this regulation is still likely to leave leeway for party-political usage.

Consider, for instance, the staffing expenditure available to members of the House of Commons, a resource within the remit of IPSA. Before IPSA was created, complaints had been brought forward to the Committee of Standards and Privileges that part-time parliamentary staff were simultaneously employed by MPs’ parties, a practice that was criticized back then but still today is nothing unusual. Party-political usage of staff is predominantly debated in terms of what parliamentary assistants ought (not) to do, not who these assistants ought to be. IPSA specifies the parliamentary functions staff can deal with and provides a model contract but MPs are still in charge of hiring their staff. They are able to reward former party workers by granting access to positions as far as they professionally qualify for the role. While having staff committed to the same political goals might be politically sensible for an MP, it blurs the line between the institutional and political sphere, which regulation aims at separating. In the wake of the expenses scandal the idea was debated that staff should be hired by the House rather than being controlled by MPs individually. This proposal, however, was not adopted.

Table 1: Examples of the Regulation of Parliamentary Resources in the UK and Australia and the Respective Leeway for Party-Political Usage

While the new regulations adopted after the expenses scandal has made the UK regulatory regime for parliamentary resources overall stricter, institutional resources important to parties are still regulated by self-restraining regimes that neither separate institutional functions from partisan ones in terms of earmarking nor are underpinned by an independent enforcement structure. An example for a resource that is very important to UK parties (due to the scarcity of direct state funding) is Short Money. Unlike the staffing expenditure, this resource that was introduced in 1974 to enable opposition parties to more effectively fulfil their ‘parliamentary’ functions stays outside of IPSA’s remit. This resource does not even out the imbalance between the executive and the legislature as institutional actors, but between government and opposition as politically defined roles.

It rests on the recognition that parties indeed profit resource-wise once taking over government (e.g., through ministerial support and access to special advisors)—otherwise the financial support accorded to opposition parties to even out the government’s resource access (instead of supporting parliamentary parties generally) would be difficult to defend. The money, in effect, flows into general party budgets. While “parliamentary business” is specified, as Prof. Keith D. Ewing, serving as an expert witness at a hearing of the Select Committee on Public Administration, pointed out: “We have a definition of parliamentary business which does not include the words ‘Parliament’ or ‘House of Commons’, which seems to be an extra-ordinary omission in terms of the use of the money.” Indeed, Article 3(1) of the Short Money resolution of May 26, 1999, declares that “financial assistance shall be available for the costs necessarily incurred in the running of the Leader of the Opposition’s Office,” which in practice means the hiring of press officers and other support staff. In effect, this resource is therefore earmarked for party-political usage rather than trying to prevent it.

That said, specific and explicit earmarking of resource usage for institutional purposes is not necessary prevent party-political usage either, if external monitoring is absent, as MPs’ communications allowance in Australia illustrates. MPs are provided with the costs of commercially printing, communicating, and distributing information for parliamentary purposes, in both hard copy and/or electronic format. The principal purpose of the entitlement is to facilitate MPs’ duties as elected representatives of their constituents and it must not be used for party business or the production of ‘how to vote material’. Party business is clearly defined as: “The production, communication of material that: is, or contains, how-to-vote material; or solicits subscriptions or other financial support for a member, political party or candidate.” Nonetheless, a 2009 report on parliamentary entitlements by the Australian National Audit Office (ANAO) referred to the ongoing and usual practice for MPs’ printing materials to be strategically coordinated and to involve the “consistent delivery of campaign messages and themes,” evidenced by party-wide advertising strategies, common text, and artwork designed to promote the interests of the MPs’ parties.

While despite these revelations to date none of the parliamentary resources in Australia are regulated by a constraining regime (defined by clear-cut earmarking and independent monitoring) Australia might soon ‘catch up’ with the UK somewhat. Earlier this year the Speaker of the Australian House of Commons used her travel entitlements to hire a helicopter to attend a party fundraiser and resigned. Amidst public outrage, the Parliamentary Expenses Amendment (Transparency and Accountability) Bill 2015 was introduced proposing not only stricter disclosure requirements and penalties for rule violations but also a stronger role of the Commonwealth Ombudsman as independent adjudicator.

Constraining regulatory regimes as adopted in the UK for some parliamentary resources make a difference for what parties and their representatives can and cannot do in public office. Yet leeway for party-political usage can still exist even if constraining regimes are adopted, depending on the nature of the resource we look at (Table 1). This has broader repercussions. The success of regulatory reforms (driven by the increasing criticism of parties’ exploitation of public privileges and a growing desire to see “governing” depoliticised) presupposes that party-political functions and institutional functions can be clearly separated through means of regulation, which research puts into doubt – at the least in systems where government-opposition dynamics dominate political decision making as the case in Westminster democracies. This, in turn, implies practical barriers against a depolitization of parliamentary politics, that some see as a means to re-establish citizen confidence in modern government.

Reforms are unlikely to be effective unless they, and the associated policy prescriptions, are driven by the awareness that when trying to regulate resource usage, preventing unfair competition (usually a central motivation to try to prohibit party-political resource usage) is only one dimension to be considered.

Party representatives in public office need to reconcile competing public claims linked to their role as lawmakers and governors and linked to their role as party politicians representing political alternatives to the citizens they represent. Hence, the increasing introduction of detailed reporting and disclosure requirements needs to be accompanied by a public discussion of what constitutes legitimate institutional usage and (potentially) illegitimate party-political usage and which of several (possibly competing) goals the regulation chosen ought to achieve.

—

This article is based on Bolleyer, N, and Gauja, A: ‘The Limits of Regulation: Indirect Party Access to State Resources in Australia and the United Kingdom, Governance, 2015 28 (3): 321–340).‘ It gives the views of the author, and not the position Democratic Audit UK, nor of the London School of Economics. Please read our comments policy before commenting.

—

Nicole Bolleyer is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Exeter

Nicole Bolleyer is Professor of Comparative Politics at the University of Exeter

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Parliamentary resources are used in party-political ways but attempts to reform are limited by reality on the ground https://t.co/GFIqEQPDAe

Canadians should read @procedurepols: The blurring of party-political & parliamentary roles hampers oversight https://t.co/Ee8G63y5aC

The blurring of party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of regulatory regimes: Th… https://t.co/ONts5swNv1

The blurring of party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of regulatory regimes https://t.co/MHZ5Rnna0i

blurring party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of regulatory regimes https://t.co/q0BScQ6jWs

The blurring of party-political and parliamentary roles can impede the effectiveness of… https://t.co/gcBlwtP9kF https://t.co/RazlO8eK2l