Making the breakthrough into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller political parties

Establishing the impact of legislative representation on parties’ subsequent electoral outcomes is very difficult due to how different parliamentary and non-parliamentary parties look. To address this problem, Elias Dinas, Pedro Riera and Nasos Roussias used an element that is quite common in multiparty systems – that is, legal thresholds of representation at the national level- and compared parties that are slightly above and barely below it. Looking at all post-WWII democracies with a national threshold of representation, they show that presence in parliament increases parties’ vote shares in the next election.

Could UKIP suffer because they didn’t make the breakthrough? (Credit: altogetherfool, CC BY NC 2.0)

In all democratic countries, there are small political parties. Some of them manage to survive and increase their electoral support over time. Others are less successful and see their appeal diminish election after elections until they cease to exist. How can we explain these divergent patterns? We argue in a recently published paper that small parties entering parliament are more likely to endure and grow electorally in the future. The lesson for small parties is clear: if they join the club of parliamentary insiders, they should expect to improve their performance in future elections; if they do not, they will run out of time soon.

In this regard, parliamentary and non-parliamentary parties are not exchangeable, but differ in several important aspects that explain their different electoral performance in the first place. For example, appealing candidates do usually run under the label of successful parties. Likewise, parties that obtain parliamentary representation enjoy more organisational capacity than those that fail to enter the legislative chambers. Attributing any variation in subsequent parties’ vote shares to the fact that some previously became parliamentary whereas others did not runs the risk of neglecting the role of these various traits that explain why some parties are more electorally successful than others in the first place. To see whether there is a real effect of winning at least one seat on the future electoral fate of parties, we need to design a quasi-experimental environment in which insider and outsider parties have everything in common but one feature: their parliamentary status. How can we do that? The basic idea is simple.

For example, let us take the case of Germany. In general terms, only parties obtaining at least 5% of the second vote at the national level are eligible for the allocation of PR seats. Consider two parties in that country that get 5.1 and 4.9 percent of the second vote at the national level in one election, respectively. Although they may differ in various respects, it would be safe to assume that such differences are minimal. However, they would diverge in one crucial aspect for this project –that is, their parliamentary status- provided that the latter does not have three candidates directly elected in the single-member districts. In other words, the former would have secured parliamentary representation because it has passed the legal threshold whereas the latter would not obtain any seats because it has failed to cross it. Even more importantly, it could be argued that parliamentary representation is just a matter of (bad or good) luck for parties in the vicinity of the threshold.

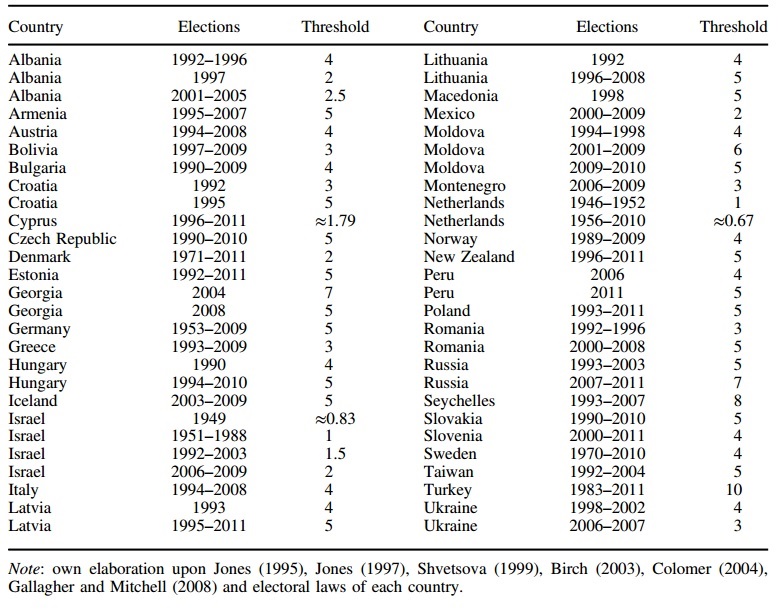

Bearing these considerations in mind, we first identified democracies that had employed a legal threshold of representation at the national level at least once since 1945. We then created an original data set that included all parties that had run in elections under that institutional feature. In Table 1, we report the list of countries, elections and thresholds that are included in the analysis. As can be seen, we have a diverse list of thresholds that varies widely across countries and over time, with the Netherlands after 1956 constituting the minimum (0.67 percent) and Turkey the maximum (10 per cent). For each election in our data set, we obtained the vote share of all parties and examined whether those barely exceeding the threshold at one election were performing better in the subsequent election than those that just missed it.

Table 1. Legal thresholds of representation at the national level around the world, 1946-2011

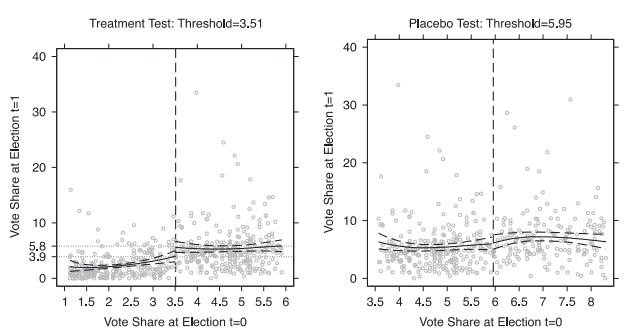

In Figure 1 below, each dot represents one party. The horizontal axis depicts the vote share of the party at one election, and the vertical axis depicts the vote share of this same party at the immediately subsequent one. The farther to the right the dot is in the graph, the better the performance of the party at the first election; the higher the dot is in the graph, the better the performance of the party at the second election. If the dot falls on the right side of the vertical dashed line, the party has crossed the legal threshold and has obtained parliamentary representation at the first election. The key message is the gap in parties’ vote shares at the vertical line that separates those that enter parliament from those that do not. The vote share of parties in the second election is much higher for those parties that just exceeded the threshold in the first one (i.e., 5.8 percent), compared to those that had just missed it (i.e., 3.9 per cent).

Figure 1. The effect of parliamentary representation at t0 on vote share at t1: Excluding cases with vote share at t1 higher than 20%

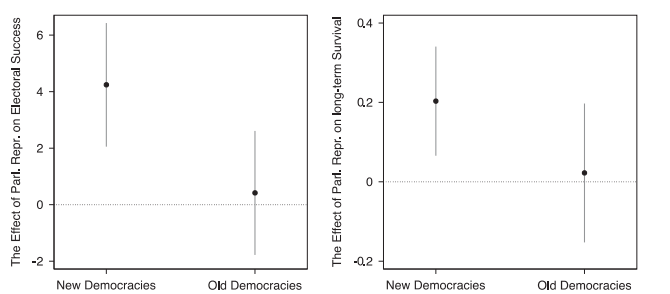

We then examined whether achieving legislative representation was more helpful for small parties in new democracies. In non-established party systems, parties lack ties with voters and need the organisational resources generated by the Parliament in order to guarantee their survival and increase their electoral fortunes. Figure 2 below shows the effect of parliamentary representation for the two groups of countries: new democracies and old democracies. The first panel presents the results for electoral success. The effect of obtaining at least one seat only seems to boost parties’ vote shares in new democracies. The second panel of Figure 2 looks at party survival rate. Parties that gain foot in the parliament are significantly more likely to run under the same label at the next elections in new democracies.

Figure 2. Distinguishing between new and old democracies, party vote share and long-run party survival

To sum up, parliamentary representation is clearly an important element in understanding the electoral performance of small parties in new democracies but also in old ones. This effect could be attributed to at least four different benefits parliamentary parties enjoy:

- participating in the policy-making process

- obtaining public funding

- increasing media visibility, and;

- spreading the perception of electoral viability among the electorate.

Finding out which is the most relevant driver of this effect among the aforementioned mechanisms and exploring its impact on other political outcomes constitute some next steps for this project.

—

Note: See the author’s full paper for more information on these calculations. This post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Elias Dinas is Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics and International Relations of Oxford University. His research interests include the dynamics of political socialisation, comparative political behavior and political methodology.

Elias Dinas is Associate Professor in Comparative Politics at the Department of Politics and International Relations of Oxford University. His research interests include the dynamics of political socialisation, comparative political behavior and political methodology.

Pedro Riera is Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Sciences of the Carlos III University of Madrid. His research focuses on political institutions, particularly electoral systems, and voting behaviour, involving the use of innovative research designs.

Pedro Riera is Assistant Professor at the Department of Social Sciences of the Carlos III University of Madrid. His research focuses on political institutions, particularly electoral systems, and voting behaviour, involving the use of innovative research designs.

Nasos Roussias is a Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of Sheffield. His research focuses on the interaction between institutions, parties and voters, with a particular emphasis on the strategic behavior of parties and voters, electoral fraud and party systems in new democracies.

Nasos Roussias is a Lecturer in the Department of Politics at the University of Sheffield. His research focuses on the interaction between institutions, parties and voters, with a particular emphasis on the strategic behavior of parties and voters, electoral fraud and party systems in new democracies.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Breaking through into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller political parties @eliasdinas https://t.co/LcoOK5r8qt

Imprescindible: Making the breakthrough into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller political parties https://t.co/viXCS0CsrO

Being present in parliament assists a party in gaining more votes, says @EliasDinas et al on @democraticaudit: https://t.co/twhvICp6ql

Making the breakthrough into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller political parties https://t.co/1IeQwOVDLT

Making the breakthrough into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller political parties https://t.co/KnOjxScbHL #Option2Spoil

Having just one MP opens the door to increased electoral success. https://t.co/Mvzdjw1d7x

Making the breakthrough into Parliament boosts the electoral success of smaller… https://t.co/aWwtm7KJ3r https://t.co/n3KF1nL8Hr