Parliamentary administrations: an important pillar in the parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs

National Parliaments were given new powers of control in the most recent European Treaty, the Treaty of Lisbon. The aim was to bring EU issues closer to the citizens and to generate more political debate on a European Union that is often seen as being overly bureaucratic and technocratic. However, parliaments are not just composed of elected politicians – they also rely on a bureaucracy. Drawing on a recent paper in West European Politics, Anna-Lena Högenauer and Christine Neuhold ask to what extent parliamentary control of EU policy-making was performed by administrators, rather than elected politicians? And is the involvement of administrators a problem or in fact beneficial for parliaments?

National Parliaments were for a long time perceived as “losers” or “late-comers” in EU politics. Despite the fact that more and more policy-making competences moved to the European level with every new EU Treaty, the role of national parliaments was confined to the ratification of EU Treaties and the control of their national government’s activities in the Council of Ministers. Until the mid-2000s, they had few means of influencing the EU institutions directly. However, in 2006, the President of the European Commission, José Manuel Barroso, initiated a “political dialogue” with the national parliaments. The parliaments could now send their comments on EU policy projects to the European Commission, and the Commission would respond to their concerns.

In 2009, the Treaty of Lisbon then further improved the information rights of national parliaments, who now received a wide range of policy-documents directly from the European institutions. In addition, Protocol 2 of the Treaty created the so-called “Early Warning Mechanism”: National parliaments are sent all EU legislative proposals and have eight weeks to comment on them. However, they are supposed to only comment on whether the proposals are in line with the principle of subsidiarity, i.e. on whether the proposals should be developed on the European level, or rather on the national or regional level. Each national parliament has two votes (in bicameral parliaments, each chamber has one vote), and if 1/3 or critical votes are cast in the form of “reasoned opinions”, i.e. objections on grounds of subsidiarity, then the European institution that has put forward the draft has to review the proposal. The institution in question is not obliged to withdraw the legislative proposal or to amend it, but in practice there is great political pressure on it to respond to the criticism.

But how do these new powers affect the organisation of national parliaments and their work routines? Many national parliaments were eager to use the new opportunities, but in order to do so they have to monitor about 25,000 EU documents per year, out of which about 1,000 are deemed “core” legislative documents. There is thus a lot of information that needs to be filtered. As a result of this challenge, parliamentary administrations have become involved in the scrutiny of EU affairs to a substantial extent.

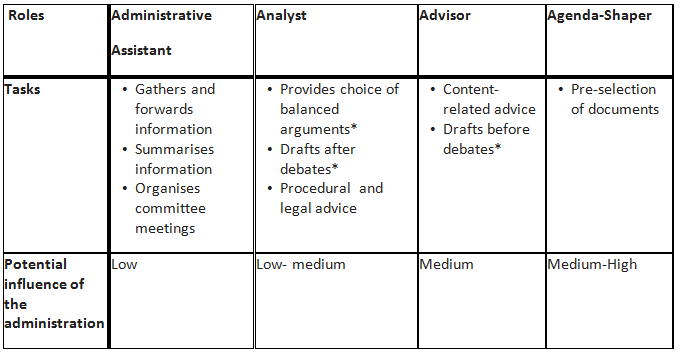

In our research, we distinguished four potential roles for national parliamentary administrations (Table 1). Firstly, under an administrative analyst model, the administration would simply forward the information from the European level to MPs without further comment or provide politicians with very short summaries of documents.

Secondly, an analyst-type administration would offer legal and procedural advice on the options available to parliament. In addition, they could be involved in drafting documents on the basis of debates.

Thirdly, the administration could play an advisory role in which its tasks might include the provision of specific content-related advice (for example on whether something constitutes a breach of subsidiarity).

Fourthly, an administration could play the role of agenda-shaper if it were tasked with the pre-selection of documents that are particularly relevant for parliament or specific committees. By recommending certain documents for further consideration, the staff could influence what kind of issues are likely to make it onto the parliamentary agenda.

It is also important to note that the first four roles are incremental. In other words, staff playing an advisory role may well also perform the tasks in the categories of analyst and assistant.

Table 1: Roles and tasks of parliamentary administrators in EU Affairs

*These tasks and distinctions were derived from the in-depth interview data.

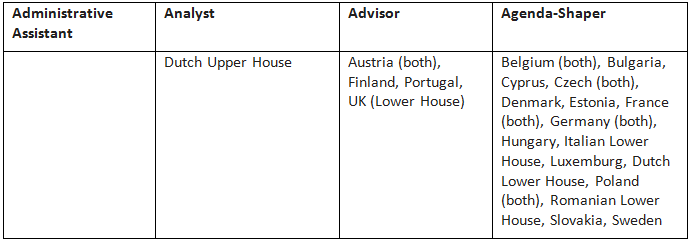

We have data for 28 chambers (some of the national parliaments being bicameral parliaments). As we can see from Table 2, none of the administrations only forwards or summarises information. In fact, the vast majority of administrations provides advice on procedures, on the content of documents and pre-selects potentially problematic documents. Thus, they can shape the agenda of their parliaments to some extent. The administrations of five of the chambers, including the UK House of Commons, at least play an advisory role, where they suggest procedural options and provide some content-related advice. On the whole, parliamentary administrations thus contribute substantially to the scrutiny of EU affairs in national parliaments, often suggesting which policies merit further debate.

Table 2: Roles of Parliamentary Administrations (in 2013)

However, if parliamentary administrations play such an extensive role, is this a problem for European democracy? Is bureaucracy trespassing on the role that should in fact be assumed by directly elected members of parliament? Our research suggests that so far that the role of parliamentary administrations is not problematic per se.

Firstly, one important reason why administrators can play a substantial role is trust. MPs “allow” administrators to preselect documents and to provide procedural and substantive advice because they trust them to filter the information on the basis of the priorities of parliament.

Secondly, the final decisions are still taken by elected politicians, at least for the cases we studied. The pre-selection of documents by administrators generally requires the approval of committee chairs or the parliamentary committees as a whole. The final draft of reasoned opinions is also voted upon by the committees or plenary. The substantial “delegation” to administrators is thus the result of a division of labour that allows MPs to devote their time to the most important debates and issues.

—

This post is based on a recent paper in the West European Politics Journal

Note: This post represents the views of the author and not Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Anna-Lena Högenauer is Adjoint de Recherche at the University of Luxembourg . She is a co-editor of the OPAL and Pademia Online Paper Series on parliamentary democracy in Europe and has published widely on multilevel governance and multi-level parliamentarism in the European Union.

Anna-Lena Högenauer is Adjoint de Recherche at the University of Luxembourg . She is a co-editor of the OPAL and Pademia Online Paper Series on parliamentary democracy in Europe and has published widely on multilevel governance and multi-level parliamentarism in the European Union.

Christine Neuhold is Professor within the Department of Political Science, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences (FASoS), Maastricht University. Since 1 May 2013 she holds the Special Chair of EU Democratic Governance. She has published widely on EU integration, with a focus on the role of parliaments and committees.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Parliamentary administrations: an important pillar in the parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs https://t.co/LzDjMwEu0b

Parliamentary administrations: an important pillar in the parliamentary scrutiny of EU affairs https://t.co/MxU6br0OPj