Interview: Professor Susan J. Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics on both sides of the Atlantic

Democratic Audit’s Sean Kippin and USApp’s Chris Gilson recently interviewed Professor Susan Carroll, the Author of More Women Can Run: Gender and Pathways to the State Legislatures to coincide with an event at the LSE. They discussed American and British politics, and the different challenges faced by aspirant female politicians and established woman leaders.

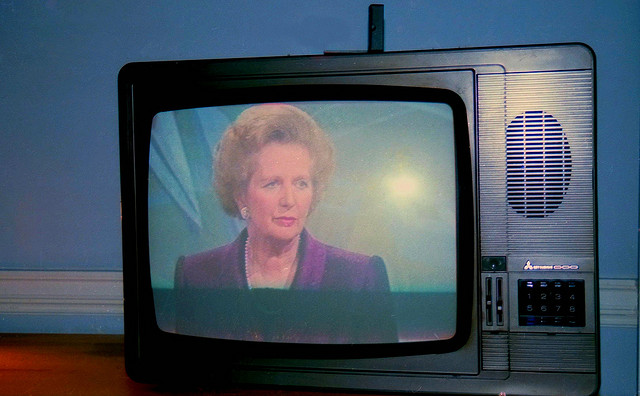

Credit: R Barraez D’Lucca, CC BY 2.0

SK: Do women in the UK face different barriers to being elected to office? And do you think that the UK having more of a multi-party system and a more generous welfare state have any bearing on female representation?

Well, you still have a First Past the Post system. And clearly, the countries that have that kind of system lag behind those countries which have party list [electoral systems]. So the UK and US share that. I think a lot of the problems are very similar across the two countries, and the gender stereotypes that exist are much the same. Margaret Thatcher for example, who I do know a bit about, faced some of the same problems that Hilary Clinton faced, in the sense that when she ran in 2008 she had to establish her “toughness” but a lot of people thought she wasn’t “likeable” enough and that she wasn’t sufficiently showing her human side, her feminine side.

I think Margaret Thatcher worked out how to balance that out, because she was a very tough person but she always wore her signature pearls and carried her signature handbag and managed to create a balance between masculinity and femininity. A man doesn’t have to worry about those kinds of things. I think there’s no question that women in this country still get asked about children and who is responsible for childcare when they’re running for office. That happens in both countries, so I think there’s certainly a lot in common. It sounds, from the outside, as if the Labour Party has had a little bit more success in being progressive.

SK: That brings me on quite nicely to the next question that I was going to ask, which is about All Women Shortlists, which the Labour Party uses. Do you think there’s a case for expanding that to the US – but also would it be seen as a ‘bridge too far’ by US voters?

We have a problem in the United States talking about “quotas” – we can’t use that word. Of course, quota systems have done a lot to promote the representation of women in a number of different countries. Having women on a party list is certainly a form of quotas, but we can’t use that word freely because of the history of affirmative action in the United States. So the minute the subject comes up people assume that it represents unfair advantage.

That said, oddly enough, we do have some quotas in American politics: we have gender quotas for delegates in the US Democratic Party, for example. There are also some states where they have equal representation of men and women on certain boards commissions. Also, there is a history within the party structures themselves of women being equally represented on platform committees – the major committees of the parties. So it isn’t like we don’t have it but we don’t use the word.

It’s very difficult to see how you might implement it in the United States. Our system of elections is so different, it’s really district and candidate driven rather than party driven. And so, people get elected less based on their party and more on the composition of their districts so we don’t have lists of that kind. So I can’t forsee it happening.

SK: To go back to Margaret Thatcher who you brought up in response to one of my previous questions. Do you think its detrimental in the long term that women have to adopt an almost male persona in order to be taken seriously?

I think the answer to that is partially yes, but there’s a difference between the women who are first and the women who follow. Because the women that are first open doors, and they make it possible for the women who follow behind them to exercise a bit more flexibility in terms of their persona. Of course, Margaret Thatcher was also from the Conservative Party, so wasn’t going to push too hard for gender equality at that time. I think this would also be the case now with a Republican presidential candidate, who have a different approach to the Democratic Party in terms of gender issues, which feminists find less satisfactory, generally speaking.

But there’s no question that the first woman has to, generally speaking, fit a certain kind of mould. Then hopefully that cracks the mould, if not breaks it, and that allows for more opportunities for those women that follow. And once it becomes normal to have women, I think you see a variety of different kinds of women in different kinds of styles. Certainly in the US Congress, you see lots of women adopting different kinds of personas and styles and different kinds of roles and ideologies.

CG: One thing we don’t think about a lot is US state legislatures and regional politics. The Republicans control 35 or so of the state legislatures. Do you think that in terms of increasing women’s representation in those areas it’s a case of waiting for the Democrats to win those seats back and then suddenly you’ll have much better gender representation? Or do you think the Republicans can eventually embrace action to bring about a greater degree of gender equality?

That’s an interesting question, because what’s happened at the state level over the past couple of decades is that the Republicans have controlled more state legislatures and have had more opportunities to make policy. But those opportunities haven’t opened up too much for women. So what’s happened is that the representation of women has been pretty flat for the Republicans. Despite the fact they have made great gains across the board. However there are those within the Republican Party – Republican women themselves – who serve in office who are pushing to recruit more women.

There is a little bit of an ideological problem because we have a gender gap and more women in the United States identify with the views expressed by the Democratic Party than the Republican Party. So, they are fishing in a smaller pool on the Republican side, but they aren’t taking advantage of that pool. The Democrats aren’t taking advantage of their pool either, by the way! So I don’t think it’s a matter of waiting for the Democrats to win back those seats and legislatures. More needs to be done on the Republican side. There needs to be more infrastructure in terms of recruiting and supporting female candidates on the Republican side.

SK: Do you think first of all whether Hillary Clinton can win the Presidency in 2016, and what challenges she’s likely to have to face and overcome in order to do so?

I do think she win, but its an uphill battle. If you look at the demographic changes that have happened in the US, I think things look good for any Democratic candidate and although we don’t know who the Republican candidate is going to be, it’s a very narrow path for the party as a whole to win the presidency – the opposite of congressional elections. However in Presidential elections, the growth of the Latino population more than anything else makes things easier for the Democrats. So too does the increasing tendency of younger voters to identify with the Democrats.

So I think Hilary Clinton has a really good opportunity and I think some of the things se faced the last time will not be a problem this time. Things like proving herself to be sufficiently experienced. Almost no one doubts that she is sufficiently experienced to be President. She has also proved her toughness. In this election she needs to do more to talk about the historic nature of having a woman president.

And I think she needs to do more to talk to woman voters. I think the people who ran her campaign [in 2008] weren’t keen on her doing that, and it wasn’t until her concession speech really that she talked about being a woman. In fact, she did quite the opposite. This time she needs to find a way to look like you’re an agent of change: that’s very difficult to do when your name is Clinton, and you’ve already run.

But I think talking about the historical element gives her more of a claim to being the ‘change’ candidate. I think this time she’ll face questions about her age, and I do think that’s a gendered thing. She will be 69 in 2016, and Ronald Reagan was older than that when he was first elected. There are already questions being raised. [Kentucky Senator] Rand Paul has been raising a lot of questions about her age and focussing on that, so we can expect that to be an issue. Rush Limbaugh asked whether we “really want to see a women age in office” – how awful that would be!

She also just became a grandma, and we’ve heard questions being raised about whether this will take her attention away from the job at hand. Mitt Romney has 23 grandchildren, and no one ever raised that question about him. But I think she’ll actually take the grandma issue and use it as a way to connect with voters and make her more likeable, warmer and relatable. What Americans really want – and this is what we famously hear – is a President that you can have a beer with – and that’s going to be her challenge. Strangely enough, that is part of American politics!

—

Note: this post represents the views of the interviewee and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Susan J. Carroll is Professor of Political Science and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University as well as Senior Scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) of the Eagleton Institute of Politics.

Susan J. Carroll is Professor of Political Science and Women’s and Gender Studies at Rutgers University as well as Senior Scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) of the Eagleton Institute of Politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Representation of women in politics; a comparison between US and UK. Similar issues of sexism; https://t.co/DPdnKsdtdh

Professor Susan J. Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics via @democraticaudit https://t.co/5gh2gqX4OM Comparing Hilary to Margaret

Interesting interview over @democraticaudit on barriers to women’s participation in politics for US/UK women https://t.co/jJst5QQ8Pi #GE2015

Interview: Professor Susan J Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics on both sides of the Atlantic https://t.co/Wr0txjRrMi

Interview: Professor Susan J. Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics on both sides of the Atlantic https://t.co/xKJssm83YB

Good analysis -> Interview: Professor Susan J. Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics via @democraticaudit https://t.co/QnwnB25n0U

Interview: Professor Susan J. Carroll on the barriers facing women in politics on both sides of the Atlantic https://t.co/yX9rhqzZat