Online platforms differ in their capacity to affect public opinion and increase public knowledge of the EU

How do European citizens receive what little information that they do about the policies and activities of the European Union? Laura Sudilich shares research which shows that the mainstream media – encompassing print, online, and TV – continue to dominante, despite the greater suitability in some respects of the internet. She shows that only online platforms that host well-vetted information tend to be effective in increasing knowledge and affect opinions.

Credit: Jim Killock, CC BY ND 2.0

The quality and availability of relevant information is vital to citizens’ capacity to learn about politics, their ability to link political preferences to parties and assess the performances of institutions and political actors. In most instances, people gather politically relevant information via the mass media rather than though direct interactions with political elites.

When considered in relation to the formation of opinions, the gathering of political awareness and, voting behaviour in the context of the European Union, the mass media are key actors. European citizens typically do not experience any direct contact with EU level institutions. Thus, they forcefully rely on mass media when (in)forming their opinions about the EU. Additionally, the widespread ignorance of the European Union (hereafter EU) politics and policies among members of the European public is notorious and persistent.

Over one third of Europeans are unable to name any EU institution; the percentage of citizens claiming to know a little or nothing at all about ‘the people who run the various EU institutions and the leaders of the EU’ is a striking 73%. A similarly high number of subjects (74%) reports to know a little or nothing at all about ‘The allocation of roles played by the various institutions (who does what?)’. The mass media could potentially contribute to enhancing public understanding of European institutions and policies.

In a working paper co-authored with Dr. Leonardo Baccini, we take the first step to addressing whether consuming online information about the EU is responsible for variation in public opinion towards it and if this process bypasses or encompasses political knowledge. The Internet provides a potentially unlimited amount of information. It also offers an array of heterogeneous sources, from credible news producers to user-generated content, whose quality and reliability are highly diverse. On traditional media, publishers and regulatory authorities act as gatekeepers on what can be broadcast or printed and, media editors, through the process of indexing select what is relevant for the public to know.

These boundaries only apply to certain spaces online, as the very notion of information producers has changed. Next to traditional news produces, a multiplicity of actors now publish information that is available to a potentially very large number of Internet users. Bloggers, citizens-journalists, audio-visual producers constantly upload information that can instantly spread, by sharing via Social Networking Sites, blogs and microblogs. As a consequence of the dramatically changed structure of information production, online spaces vary dramatically in the heterogeneity of their content and in the extent to which they host unverified versus verified facts.

For instance, the website of a major newspaper is likely to publish content that is vetted and has been provided by accredited sources. At the other end of the spectrum, platforms like blogs and forums are, by definition, aggregators of comments and opinions. Moreover, user-created content is prominent on popular platforms like Facebook and Twitter. Therefore, users can be exposed to a myriad of different pieces of information that may or may not translate into politically relevant knowledge. In general, the information we acquire via the mass media can translate into in-depth knowledge, superficial acquaintance or even result into no knowledge as a function of being, unclear, noisy or redundant.

While absorbing redundant information is a possibility when gathering information via any media, the Internet maximizes potential for amplification of noise by creating an environment where noise and signal are often indistinguishable. Therefore we empirically separately analyse the effects of platforms that hold strong potential for the amplification of noise (‘Online social networks’ or ‘Blogs’ or ‘Video hosting websites’ labeled Miscellaneous Websites) from those that are most likely to maximize fact-cheeked information (‘Traditional media websites’, ‘Institutional and Official websites’ labeled Fact-checked Websites), to gather a more fine-grained understanding of how the new media affect individuals’ opinions and if that happens via enhanced levels of political knowledge.

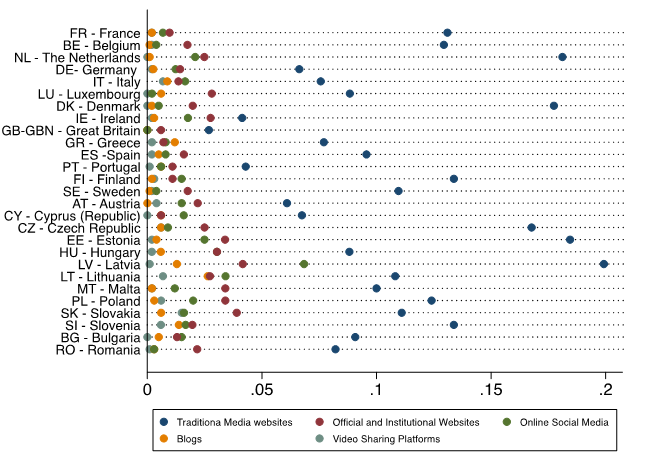

Figure 1 below shows the average distribution of what respondents indicated to be their first online source of information on EU level matters.

Figure 1. Distribution of online platforms by country averages

The take-home messages from this figure is that at the time of fieldwork the websites of traditional media outlets were, by far, the most visited platforms in every country. The second most preferred platforms to gather information on EU matters were, while the use of, and was very limited across the entire sample.

The take-home messages from this figure is that at the time of fieldwork the websites of traditional media outlets were, by far, the most visited platforms in every country. The second most preferred platforms to gather information on EU matters were Institutional and Official websites, while the use of Blogs, Online social networks and Video hosting websites was very limited across the entire sample.

Analytically we implement a causal mediation analysis model, which allows us to distinguish the direct effect of online information consumption on public attitudes towards the European Union, from its mediated effect through increases in knowledge of EU matters.

Our findings indicate that online platforms differ in their capacity of both affecting public opinion about and increasing public knowledge of the European Union. Those who search for information on European matters on the websites of traditional media or on institutions websites are more positive towards the EU, and this happens via increases in levels of knowledge of the Union. Those who perform a similar search in spaces that contain miscellaneous information do not experience changes in attitudes nor appear to learn from them. This may be due to the difficulties that users experience in separating the signal from the noise when the two are simultaneously consumed.

Traditional media dedicate relatively little attention to European matters, particularly in routine periods. While the emergence of a European public sphere is highly desirable, we have not yet seen that happening. A global, transnational, multilingual medium like the Internet carries the potential to supply all the information Europeans need and often do not find on traditional media. However, our results indicate that only platforms that host well-vetted information tend to be effective in increasing knowledge and affect opinions. Platforms that aggregate miscellaneous information do not appear to be effective at transmitting knowledge nor at impacting citizens ‘evaluations of the European Union.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit UK or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting.

—

Laura Sudilich is a Rsearch Fellow at the European University Institute

Laura Sudilich is a Rsearch Fellow at the European University Institute

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

In the UK, much of the media seems to have an anti-EU policy, often providing inaccurate information about the European Union. This has especially been the case this month with the (mis)reporting about the EU accounts and the false claims that they have never been signed off by the auditors.

See my article published today called, “It’s the British media that needs auditing”

https://www.britishinfluence.org/it_s_the_british_media_that_needs_auditing

Online platforms differ in their capacity to affect public opinion & public knowledge of EU https://t.co/PMwQEISlfa https://t.co/T8paAi9EhL

Online platforms differ in their capacity to affect public opinion and increase public knowledge of the EU https://t.co/teEad5hEGe

Online platforms differ in their capacity to affect public opinion and increase public knowledge of the EU https://t.co/X6Dp9vNvxZ