Extending the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds would deepen and strengthen British democracy

Reducing the age of enfranchisement from 18 to 16 would not just ensure that young people’s views were listened to, it would also take advantage of the growing political awareness of this age group, as evidenced by the Scottish Independence referendum campaign, evidence from overseas, and some research from the UK, according to Vittorio Trevitt.

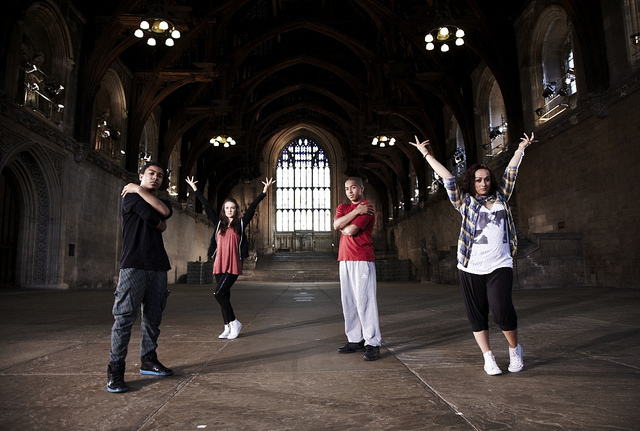

Young people dancing in Westminster Hall (Credit: somewhereto_somewhere_’s, CC BY 2.0)

It was Winston Churchill who famously said that democracy is the worst kind of government ever devised, except for all the others. The beauty of democracy is that it enables people to choose who they wish to lead them (whether it be on a local or national level), instead of being at the mercy of tyrants who may, as has often been the case in human history, plunder their country’s resources for their own selfish ends at the expense of their own people. It is probably no coincidence that a number of impoverished countries are run by dictatorial leaders while liberal democracies like Norway and Australia enjoy some of the highest standards of living in the world. It is the ability to choose under a democratic system that arguably makes democracy a worthy model for those who value freedom and prosperity the world over.

Here in Britain, the right to vote gradually became a reality for all of its adult citizens over the course of the Twentieth Century. Universal suffrage for men over the age of 21 and votes for women over the age of 30 were introduced in 1918, followed by universal suffrage for all women over the age of 21 in 1928. This was followed decades later by the Representation of the People Act of 1969, which reduced the voting age from 21 to 18. Despite these positive developments, however, there remains a significant segment of British society, consisting of over 1.5 million people, who continue to be excluded from any decision-making over the makeup of national parliaments and any future directions that our country may take. That segment is Britain’s 16-17 year old age demographic.

There already exist a number of countries the world over that allow 16 or 17 year olds (or both) to exercise the right to vote. People from the age of 16 are entitled to vote in Ecuador, Nicaragua and Brazil, and those from the age of 17 in Timor-Leste, Indonesia,[2] and the Seychelles. In Continental Europe, 16 year olds in Slovenia, Serbia, and Bosnia are entitled to vote, albeit on the condition that they are working. Closer to home, the Channel Island of Jersey lowered its minimum voting age from 18 to 16 in 2006, the first European territory to do so.[3] In 2007, Austria became the first country in Europe to allow 16 and 17 year olds to vote,[4] while some states in the USA have already carried out this great extension of democratic rights for certain elections.

There are those who would argue that the responsibility of choosing one’s representatives should not be made available to those in their late teens, believing that 16-17 year olds are too young to decide on a country’s future, and not all that interested in politics in general. From my own personal experience, however, I believe that teenagers have much to offer in the way of contributing to political change in Britain and beyond. At fifteen, I had already started to develop my political consciousness, reading publications such as “The Guardian” and “The Economist” to keep myself updated with the latest news, both at home and abroad. I also remember at school listening to pupils talk about issues related to the United Nations, the Iraq War, Third World Poverty, and baby food, demonstrating the high level of political interest that exists amongst many people in their late teens.

As an example of how young people have the potential to be actively engaged in politics, findings from Austria have shown that extending the vote to 16 year olds promotes higher turnout amongst those casting their ballots for the first time. Here in the United Kingdom, the potential of young people to play a major role in shaping political developments can also be gauged from the case of the Scottish independence referendum, where 80% have already registered to vote on the future status of Scotland. In addition, a report compiled by the think-tank Demos back in 2010 found that nearly two-thirds of 16-17 year olds were “more likely to vote than not.” According to one journalist, most young people are interested in politics, but feel alienated by politicians, whom they themselves didn’t elect. Giving 16 and 17 year olds the vote would therefore provide them with a stake in deciding their country’s future, enabling them to vote for candidates that they feel care about their interests. Based on the evidence, it is therefore a fallacy to argue that 16-17 year olds are too young and uninterested to make political decisions.

It is wrong that such a large segment of our population, one that has much to offer by way of contributing to the social and economic development of our country, should continue to be excluded from one of the basic human rights: the ability to vote. Ed Miliband has promised to give 16 and 17 year olds the vote should the Labour Party form the next government, while Nick Clegg has himself expressed support for the idea of lowering the voting age to 16. Extending the franchise to 16-17 year olds is not only socially just, but by giving over a million people a voice on how the country should be run for the first time in their lives, this could very well shape the future direction of British politics, both domestically and internationally, in the years to come.

—

Note: this post represents the views of the author and not those of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before posting. The shortened URL for this post is: https://buff.ly/1nTMlJ2

—

Vittorio Trevitt is a Humanities graduate from Brighton with a research interest in local and national politics.

Vittorio Trevitt is a Humanities graduate from Brighton with a research interest in local and national politics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Extending the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds would deepen and strengthen British democracy https://t.co/HJr0AtLbqH

AS unit 1-Democracy&Participation: Extending the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds would strengthen British democracy https://t.co/eUiazdYqri

The case for extending the franchise to 16 and 17 year-olds | #VittorioTrevitt | via @democraticaudit | @votesat16 | https://t.co/1ITnFcVHbu

Extending the franchise to 16 and 17 year olds would deepen and strengthen British democracy https://t.co/DRvRIVqykH