Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation

Young women aged 18-24 are likely less to take part in elections than their male counterparts. As part of our new series on youth participation, Jacqui Briggs explores the reasons for this, showing how women face specific barriers because of their gender and are under-represented throughout the system. She argues that politicians need to address issues that affect women’s lives such as the gender pay gap and domestic violence to show young women that politics is relevant to them.

Young women have mobilised to protest against sexual violence across the world. Credit: jonanamary, CC BY-NC 2.0

Young women aged between 18 and 24 constitute the sector of the electorate least likely to vote. Given this fact, it is worthwhile focusing upon the political education of young women and girls per se to see if there are measures that can be taken to get them to engage more with mainstream politics. Why should the focus be upon young women in particular as opposed to young people as a generic grouping? Many young women appear as equally disconnected with mainstream party politics and participation in elections as their young male counterparts, and their attitudes and behaviours tie-in with the findings of the burgeoning literature on young people and politics. But while they are clearly interested in many political issues, young women often face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation and democratic representation.

It has been widely acknowledged that the under-representation of women in formal politics highlights the continued gender stratification of political power. As the Sex and Power report recently noted, it is ‘now almost 40 years since the Sex Discrimination Act was passed, and over 80 since women got the right to vote equally with men, yet women, still, are all too often missing from politically powerful positions in the UK’. In 2014, only 22.5 per cent of representatives in the UK Parliament, 32 per cent of local councillors, and 33.3 per cent of UK MEPs were female.

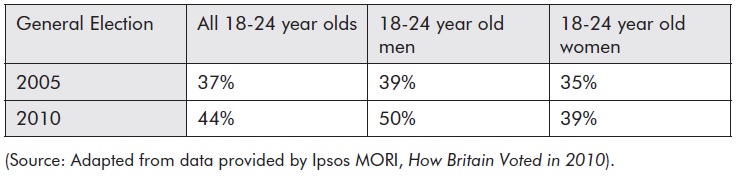

Women’s voices and physical presence are still peripheral in British politics in the 21st century. This is somewhat surprising considering that women (comprising 52 per cent of the electorate) have the potential to have a significant impact upon the outcome of the electoral process. Women’s votes, or in this case young women’s votes, should not be taken for granted or overlooked. But although young women may be no less politically engaged and informed than men, they do appear to be less active. There is a worryingly low turnout of young women in the 18-24 year old age bracket when compared to their male counterparts (see Table 1). Although the figures for both men and women were up slightly on the 2005 general election, young women in this age category were the least likely to cast their vote at the last general election.

Table 1: Young Men and Women and Turnout

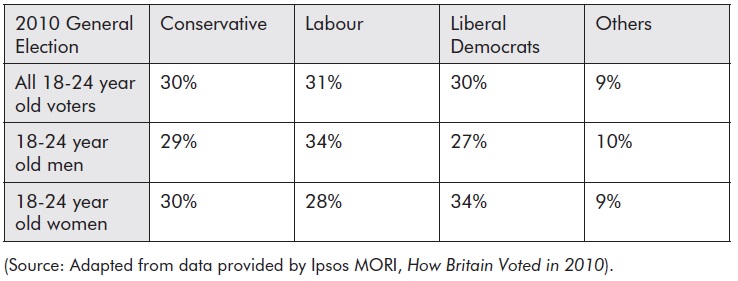

Sarah Childs notes there are differences between younger and older women in terms of political affiliation and priorities. Young women tend to vote more for parties on the centre-left of the ideological spectrum than their older counterparts and are motivated by issues such as education and family policy (see Table 2).

Table 2: Young People and the 2010 General Election: How they voted

In terms of their political choices, young women do not however appear to differ too much from their male counterparts in how they voted at the 2010 General Election. While the majority of young men supported the Labour Party, the majority of young women voted for the Liberal Democrats.

The relative absence of young women from discussions about youth citizenship is somewhat surprising, as women’s life experiences have undergone significant change over recent years. They are, for example, more likely to remain in education or to enter paid employment. Indeed, there are more female full-time undergraduates than males at UK universities, with 55 per cent of current cohorts female compared to 45 per cent male. However, disaggregation of the data in relation to youth unemployment reveals that young women are more likely to be unemployed than young men. Such factors are generational and may well contribute to a future politicisation of young women who could be a powerful political voice. This noted, in circumstances where they do not enter either the world of work or academia, so-called ‘lifestyle’ choices such as young motherhood should also mean that women want and need to concern themselves with political issues and questions.

Policy proposal

The All-Party Parliamentary Group for Women in Parliament should establish an inquiry on Young Women in Politics in order to explore the reasons for and rectify the relative absence of young female representatives in local and national politics.

Politicians and policy makers may well make calculated choices to ignore or at least sideline the views and wishes of young women, especially if they are the sector of society least likely to cast their vote. It should though be of some considerable concern to those interested in the health of our democracy that more young women are not currently seeking to participate in politics. However there is a need for young women to have their levels of political awareness raised to encourage greater political participation, particularly given the continued existence of such issues as sexual discrimination and sexism within society, of the gender pay gap (currently men still earn, on average, 15 per cent more than women) and domestic violence that predominantly involves males using force against women. By addressing such issues, politicians can ensure that young women come to fully appreciate the relevance of politics to their everyday lives and are galvanised into participating through voting and other such activities.

Positive measures to actively encourage young women to see the relevance of politics to their own lives would undoubtedly prove beneficial. By building youth citizenship capacity amongst young people, it would become increasingly difficult for politicians to ignore their voices and concerns. Citizenship classes in schools, a relatively recent introduction into mainstream education across the UK in the past decade or so, might be one way of getting this important message across. By empowering young women through the development of gender-related citizenship knowledge and skills, low levels of female political representation could be redressed. Greater focus upon the lived experiences of young women in citizenship classes could also address the gender divide in terms of political participation between young males and young females. Young women, encouraged to make their voices aired and heard in schools and local communities, could finally challenge long-established notions that the world of politics, to use the old adage, is a ‘man’s world’.

—

This post is part of a series on youth participation based on the Political Studies Association project, Beyond the Youth Citizenship Commission. For further details, please contact Dr Andy Mycock. An electronic copy of the final report can be downloaded here.

Note: This post represents the views of the author and dies not give the position of Democratic Audit or the LSE. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1hWVsV5

—

Dr Jacqui Briggs is Head of School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln.

Dr Jacqui Briggs is Head of School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Lincoln.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

“Young women face sex-specific challenges that limit their political participation” via @democraticaudit https://t.co/MGdxFY1KsO #sexequality

Young women face gender-specific challenges limiting political participation | by @JacquiBri Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/WtvlbWNqvw

Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation https://t.co/YX5fZiKTyj

“Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their pol participation.Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/2RSqI4b9U4” @OlatzRibera

Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation : Democratic Audit UK https://t.co/l5XyDf4agj

Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation https://t.co/czsWYomWl8 #gender #feminism

Young women face challenges that limit their political participation https://t.co/tqYuaBBpjk might be of interest to @everydaysexism

I’m not sure about the supposed link between politicians addressing the gender pay gap and domestic violence and “ensur[ing] that young women come to fully appreciate the relevance of politics to their everyday lives.” This seems to assume that these issues are (or have a strong potential to be) particularly prominent concerns for young women. But I have seen no evidence for this. On the contrary, there seems some evidence that young women are particularly antipathetic to ideas perceived as feminist and hold even less tolerant attitudes towards victims of rape than men.

Interesting post by Jacqui Briggs of @ul_ssps on the challenges which limit political participation by young women https://t.co/pQ3zNk6IQk

Young women face gender-specific challenges that limit their political participation https://t.co/yPVovc3Tqp