Individual electoral registration may further marginalise voters from ethnic minorities

The participation of ethnic minority groups in elections is vital, as these groups face multiple disadvantages often as a result of their new arrival status, and may also be victims of racial prejudice and discrimination. In the UK, however, ethnic minorities are significantly under-registered to vote. Dr Maria Sobolewska and Professor Anthony Heath argue that the main reasons for this democratic deficit are lack of knowledge of eligibility and socio-economic marginality. They also suggest the future is bleak with new registration rules likely to further depress levels of minority registration.

Diane Abbott was Britain’s first black female MP. Credit: Jamaica50_Launch008, CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Are minorities excluded from voting, or do they choose not to participate?

Despite the legal advantages of British ethnic minorities in terms of the right to vote, which is very generous in comparison to many other countries (and extends to all citizens of the Commonwealth and Pakistan), minorities remain under-registered to vote. While only 7 percent white British eligible voters remain unregistered, the numbers for minorities are much worse: 15 percent for Pakistani minority, 16 percent Caribbean, 17 percent for Bangladeshi, 18 percent Indian and a shocking 28 percent among eligible British residents of African origin.

Yet, as we have shown elsewhere those who were registered voted as much as the white British, which poses a question as to why so many do not register in the first place? Are all those who mean to vote registered and the rest chose to opt-out of British politics? Or are they excluded from the process?

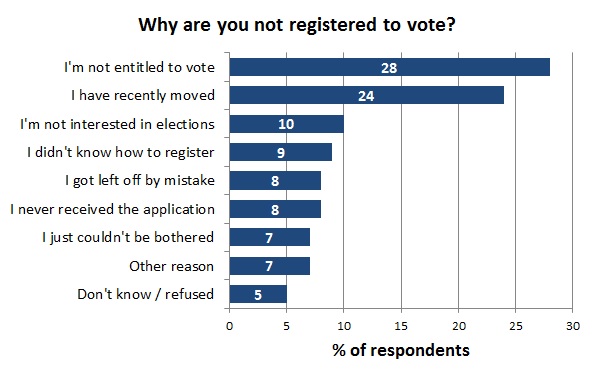

Looking at Figure One below, the answer is clear that minorities do not generally opt-out. Only 10 percent of those not registered said that they were not interested in elections and another 7 percent stated that they could not be bothered. By far the most significant cause was lack of knowledge, with 28 percent not knowing that they are even eligible (despite the fact that a clear majority in our survey were definitely eligible on the basis of their Commonwealth citizenship), and further 9 per cent didn’t know how to register. The next most common cause for not registering was having recently moved (24 percent) – which is the dominant cause among white British – and not having received the form (8 percent).

Figure One: Reasons for not being on the electoral register, members of ethnic minority groups in the UK

Source: Ethnic Minority British Election Survey

Source: Ethnic Minority British Election Survey

In our survey, the Ethnic Minority British Election Survey (EMBES), we were only able to ask those who told us that they were not registered, but in carrying out the vote validation against the marked-up Electoral Register, we discovered that some people, who said they were registered, were not. Also, we were only able to ask the reasons for not having registered to our ethnic minority sample, and not to the main British Election Study (BES) sample, which provides a white-British comparison. Therefore, we also ran an analysis of all those who were not registered both in the BES and EMBES where we included all the usual socio-economic predictors of voter participation.

As a result we found two things: firstly, most of the reasons for not registering are common among white-British and ethnic minorities; secondly, the main reasons for under-registration are socio-economic marginalisation: being young and living in privately rented accommodation. Other reasons were lack of a sense of duty to vote, and among minorities: years since arrival (among immigrants) and lack of English fluency.

Apart from a sense that voting is a duty, all these predictors relate to a marginalised position in British society. Young people are marginal relatively to older groups, people living in privately rented accommodation are marginal in comparison to owner-occupiers or even social housing tenants, who enjoy long term rental contracts and better quality control of their accommodation. Lack of local knowledge and poor English also obviously place those minorities with more recent arrival at the margins of society, but even for those minorities born here, a hard to overstate issue of racial discrimination adds to the picture of the overall socio-economic marginality of ethnic minorities.

Potential impact of individual electoral registration

Since the beginning of 2014 the electoral registration system has been changed from household registration to individual electoral registration (IER). Despite many problems with the household registration, some minorities were benefiting from this system, as a longer established, or better informed house of household was able to register his or hers non-English speaking relatives or dependants. This was especially benefiting some South Asian communities where women are more likely to be excluded from employment outside the household and therefore are less likely to have fluency in English and knowledge necessary to fill the forms. Our survey indicated that someone else filled the registration form for 17% of minority women, in contrast to 11% of men.

Women will also be less likely to possess the National Insurance (NI) number, which is one of the government’s proposed forms of identification. The NI number may also be harder to come by for those other marginalised minorities: young, and with short term accommodation. The Electoral Commission’s poll from 2012 signalled that ethnic minorities will find it harder to find their NI number: 57% BAME respondents said it would be very easy for them to find it, while 75% of white respondents said it would be very easy for them.

Adding to this is the clear danger that the minorities who already name lack of knowledge as a main obstacle to registration will be further hurt by a poorly-advertised change of rules as Electoral Commission’s research also shows the knowledge of the reform is very poor. While the government is aware of all these issues, there are as yet no firm proposals how to deal with this.

—

Note: This post was originally published on the Ethnic Politics blog. It represents the views of the authors and does not give the position of LSE or the Democratic Audit. Please read our comments policy before responding. Shortlink for this post: buff.ly/1m268lL

—

Maria Sobolewska is a Lecturer in Politics (Quantitative Methods) at the University of Manchester.

Anthony Heath is a Professor of Sociology at the University of Manchester.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

Democratic Audit's core funding is provided by the Joseph Rowntree Charitable Trust. Additional funding is provided by the London School of Economics.

New on DA today: Individual electoral registration (IER) may further marginalise voters from ethnic minorities https://t.co/H5zBxI6rgH

Individual electoral registration may further marginalise voters from ethnic minorities https://t.co/VJGl6aypng

Individual electoral registration may further marginalise voters from ethnic minorities https://t.co/p60WVWTd5c